Drug Cartels Vs. The Cutest Mammal In The Sea

The race is on to save a spectacular stranger—the vaquita, a shy, beautiful, and mysterious porpoise, whose habitat is being plundered by criminals.

By Vicki Croke

The vaquita is a spectacular animal with bold black tracings circling the eyes and painting a smile along the lips. Photo: Barbara Taylor/NOAA.

The vaquita, a mysterious and strikingly-beautiful porpoise species, is down to a population of just 100, making it the most critically endangered marine mammal in the world. And worse, scientists say, a horrifying new development, which involves drug cartels and Chinese wildlife traffickers, could drive the animals to extinction within three years.

But not without a fight.

Vicki talks with Here & Now’s Jeremy Hobson about the future of the vaquita.

The marine mammal conservation community, deeply affected by the extinction in 2006 of the baiji, a freshwater dolphin found only in the Yangtze River in China, seems determined to prevent the same end for the vaquita.

More than 30 conservation groups from around the world have signed a letter to the Mexican president urging him to act quickly. And while an announcement from the government didn’t materialize last week, as anticipated, there’s still hope.

The vaquita, whose entire population is tucked up in the northern part of the Gulf of California, is relatively new to science, having been first described in 1958. The animals are still rarely seen. In fact, they are so shy that the best way to count them is by listening for them—making underwater recordings— rather than looking for them.

The vaquita’s entire population is tucked up in the northern part of the Gulf of California. There are no safer waters. No backup population of the vaquita anywhere else in the world.

Map data courtesy of IUCN.

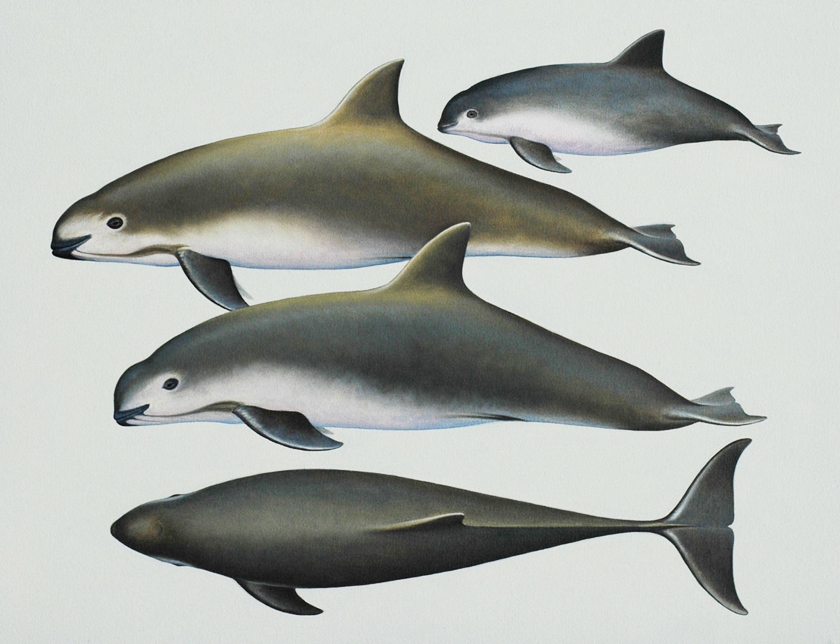

With it’s sleek body and sweet expression, the vaquita looks something like a friendly torpedo. It is the world’s smallest porpoise (four to five feet long, and 65 to 120 pounds). And it is sometimes described as the cutest mammal in the sea. That’s because the rounded face of the vaquita (or “little cow”) is so pretty: bold black tracings circle the eyes and paint a smile along the lips.

In 1986, Greg Silber, now a biologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, became one of the first researchers to study the vaquita. The porpoise is, he says, “One of the world’s rarest and most secretive animals—a species that in many ways remains an enigma to this day.”

As a scientist, Silber finds it “remarkable” that this relatively large mammal remained unknown to science until the late 1950s. On a more personal level, he is struck by the fact that his study species, the vaquita, which was first described after his birth, “may be fated,” he says, “to disappear within my lifetime.”

It’s difficult to get a detailed photo of a live vaquita, but this illustration fills in the blanks. Courtesy: Brett Jarett.

How has this happened?

For years, the biggest threat to the shy little porpoise has been shrimp and other fishing. During the fishing season, from September to June, hundreds of miles of nearly-invisible mesh, curtain-like gillnets are lowered into the waters where the porpoises live. In the process, vaquitas become a “bycatch” or collateral damage—becoming tangled in the large nearly invisible gill nets set out by the fishermen, the mammals drown.

In the past, efforts have been made to help the vaquita. In 2005, the Mexican government set up a refuge for the animals, banning fishing in a small swath of their territory. Enforcement was increased. And millions of dollars were spent to help fishermen change their practices, as conservationists worked to develop “vaquita friendly” shrimp fishing gear.

Still, the vaquita population has been declining. And, over the past three years, a new and illegal fishing operation has ratcheted up and could drive the animals to extinction by 2018.

Conservationists are hoping for an announcement soon from the Mexican government outlining a rescue plan for the critically-endangered vaquita. Photo: Paula Olson/NOAA.

Along with legitimate shrimp fisherman in the Gulf, there are now criminal fishing operations going after an endangered fish called the totoaba. And it’s all for just one part of this large type of sea bass—its swim bladder. The organ, which helps the fish control buoyancy, is used in Chinese medicine to aid in fertility among other things, and sells for as much as $5,000 a pound. According to the World Wildlife Fund, thousands of dried swim bladders are smuggled to China through the United States. Because the totoaba is endangered, it is criminals, often working at night, who are casting gillnets throughout the vaquita’s range.

They are fishing for and killing one endangered species and accidentally drowning another even more critically endangered animal in the process.

The solution is clear, writes Zak Smith, an attorney with The Natural Resources Defense Council, in his blog:

We know what’s wiping them out, drowning after getting entangled in gillnets. And we know the two fisheries largely responsible: an illegal fishery for the endangered totoaba fish and a legal fishery for shrimp. The solution is to immediately ban the use of gillnets in all vaquita habitat, helping legal fishers to transition to vaquita-friendly gear and ferreting out and crushing the illegal totoaba fishery.

But it’s tough to take on either of these fisheries. Illegal fishing is run by tough cartels. And legal fishing is the only occupation for many of the residents who live in gulf coast desert villages that offer few alternatives. Smith says he knows that making changes is difficult:

We’ve known about this problem for years and the Mexican government has been trying to reverse the decline, without success. Unsurprisingly it’s difficult to crush an illegal fishery that has the backing of drug cartels and is supplying demand for fish-bladder soup in Asia. And the shrimp fishery has continually resisted change, often with the support of Mexico’s National Fishery and Aquaculture Commission. Thousands of families in the upper Gulf of California depend on fishing for their livelihoods and it takes time and effort to change traditions and cultures. Time the vaquita does not have.

Though the situation is dire, conservationists agree that it’s not too late. There are enough animals left for the population to recover.

And that recovery is worth fighting for. Biologist Greg Silber’s recollections of studying the vaquita decades ago reveal a little bit of what the world would lose with their extinction:

We worked on a shoestring—from small boats and, on occasion from small aircraft, but we were treated to the magic of the Gulf’s natural world.

We happened upon a location where we saw a number of vaquita over the course of a few days. Then, we found them there each time we returned. This relatively small key habitat lies within the most limited range of any marine mammal. The area probably embodies just the right combination of water temperatures, surging water currents (including some of the biggest tides in the world), and an abundance of prey species.

This photo taken by Greg Silber in 1986 is believed to be the first ever of a live vaquita. And there are two in the shot: a mother and calf.

The species is Mexico’s national treasure.

I think it is fitting that we were able to see or track or photograph the vaquita only on the most tranquil of days when the water was utterly calm. It was almost as if the animal unveiled itself under these special conditions, those unusual times when the smallest ripples at the surface were seen at long distances. It was then it seemed that something of this mysterious animal, some secret of nature, was being revealed. We were scratching away, one brief sighting at a time, to piece together a basic understanding of the animal’s behavior, its ecology; to follow the small clues revealed by one of the sea’s most elusive animals that would yield a little something of its world. I still marvel at those days.

Sunburned, hungry, and tired at the end of each of those long days, we re-lived them and smiled, often commenting “did that really just happen? I wonder what’ll happen tomorrow?” I smile thinking of them now.

And scientists and conservationists from around the world will be listening closely over the next weeks for some word from the Mexican government signaling a change in the protection of this species.

5 Responses to “Drug Cartels Vs. The Cutest Mammal In The Sea”

For cute, give me a sea otter any day, especially a baby sea otter. But I wish the vaquitas well. Thank you for introducing me to a mammal I’d never heard of.

what can we do to help?

If it’s up to the Mexican government (or any government for that matter), then they have little chance. If, however, we can somehow widen the spotlight on them before they are gone, and embarrass the government into the doing the right thing and create a slice of ecotourism here, then perhaps there still is a chance for these fascinating little creatures that I too had never heard of….

“But it’s tough to take on either of these fisheries. Illegal fishing is run by tough cartels. And legal fishing is the only occupation for many of the residents who live in gulf coast desert villages that offer few alternatives. Smith says he knows that making changes is difficult:”

I disagree with you completely on the question of it being tough to take on the illegal fisherman and the cartels. The salvation of vaquita is a relatively easy thing to accomplish actually. The Mexican Navy simply needs to shut down the are with patrol boats and powerful radar. A zero tolerance policy is what it will take. Profepa has either been corrupt, incompetent or negligent in its protection.

Everyone knows how the illegal totoaba fishery works. They go out early in the morning, set their nets quickly, leave the nets in the water for 24 to 48 hours and then retrieve them in the dead of night. It is not rocket science. The political will to save Vaquita has simply not existed and the government and NGO’s have completely failed to convince local fisherman that saving Vaquita are in their best interest. Actually local fisherman want Vaquita’s to go extinct, the sooner the better as far as they are concerned.

Local fisherman even to this day still claim that Vaquitas do not exist. It is a sad state of affairs. http://worldsaquarium.com/blog/100-vaquita-marinas-are-all-that-is-left-now-its-crunch-time-for-mexico/

America should ban all seafood products from the upper gulf or even the whole Sea of Cortes until Mexico bans gill nets from the upper gulf. Mexico has proven time and time again that it is incapable of policing it’s own fisheries. Especially in the Sea of Cortes and most especially in the illegal dorado fishery that has existed for years and continues to exist. http://worldsaquarium.com/documentary-on-illega-dorado-fising-in-sea-of-cortes-el-oro-de-cortes/

Supply or demand, what is killing Totoaba? Which is the origin of the problem?

I think is demand.

The Mexican Goverment can shut down the supply, shutting all fisheries. Then buyers will have scarcity and they will offer more money for Totoaba. Buyers in Asia or the US will simply double the amount of money they offer. Just like drugs, the issue is not the producers or the fishery (Supply) . The problem is demand, by offering more and more money to buy the Totoaba, Cocaine or Heroin.

I hope people and goverments will ever come to their common sense and see that producers or fishery is a consequence of demand. We have to fight people giving away millions of dollars in order to consume TOTOABA, Cocaine or Heroin.

If we kill all fisheries or drug cartels, people who want to buy Totoaba will simple double or quadruple the amount of money and sooner or later the fisheries will flourish and the drug cartels will flourish.

We must realize that DEMAND is the origin of the problem. A society driven towards a crazy consumption spree. Which can consume any resource even if it kills the society.

Demand is the problem, please help fight Demand.

Comments are closed.