Pet CSI: How Dog And Cat DNA Nabs Bad Guys

Through veterinary forensics, dogs and cats help crack horrific crimes, including murder and rape, by doing nothing more than shedding, drooling, urinating, defecating or bleeding.

By Vicki Croke

On Sept. 14, 2000, Wayne Shumaker, 58, Corby Myer, 30, and Lynn Ganger, 54—three carpenters building a barn loft at an upscale property near Lakeville, Indiana—were bound and shot execution style during an armed robbery. Less than two years later, the triggerman in the case, Phillip Stroud, was found guilty on all three counts of murder and sentenced to life in prison. The criminal was done in—at least in part—by the dog droppings he had stepped in during the commission of the crime. It turns out that dog feces not only messed up his sneakers, but his defense too. It was a simple mistake that was exploited by the prosecution using some new and very sophisticated science. Samples from Stroud’s sneakers were compared to dog feces at the barn. Through DNA analysis (as they exit, feces snag DNA-carrying epithelial cells from the colon), the specimens turned out to be a perfect match—proof positive that the defendant had been present at the scene of the crime.

It’s one case among hundreds, if not thousands, of human crimes being solved by the emerging science of veterinary forensics, which can help catch and convict murderers and rapists, not to mention poachers and animal abusers.

Vicki spoke with Here & Now’s Robin Young about the emerging field of animal forensics:

Since 1996, when the first case using animal DNA evidence was presented at a trial in Canada, dogs—and cats—have been helping crack horrific crimes, including murder and rape, by doing nothing more than shedding, drooling, urinating, defecating or bleeding.

The material, with its genetic signature, can act like a tag tying criminals to victims and to crime scenes. And there’s lots of it everywhere. Pets are ubiquitous—there are 70-80 million dogs and 74-96 million cats owned in this country and most of us don’t need a crime scene investigator to tell us how hard it is to avoid all that fur.

Elizabeth Wictum is a scientist who’s put away a lot of bad guys on the scientific strength of those hairs—probably about 500 by her estimate in the last 15 years. She’s served as the director of the Veterinary Genetics Laboratory at the University of California Davis (VGL), the lab whose analysis and testimony helped convict the murderer with the soiled sneaker in Indiana. It’s the only lab in the United States accredited by the American Society of Crime Lab Directors to do such DNA testing on cats and dogs. Though they even do work outside the country–helping Scotland Yard in the case of a stabbing death, for instance.

What Wictum has found over the years is that testimony from forensic vets not only helps bring guilty verdicts in trial, but it often results in cases not even having to go to trial. Just hearing about the DNA evidence that implicates them will often motivate defendants to plea bargain. The science—just the kind that jury members are accustomed to seeing on CSI-type TV shows—is often a powerful a trump card.

It’s accepted in court with the respect that all forensic fields receive. The work itself is done almost exactly as it is in labs that test human DNA.

Wictum says:

“People are always amazed that we can do the same thing in animals. But if you think about it, people are just another species. And so all those tools that are used on humans, we can use on animals.”

The lab work comes in two stages: First, the crime scene DNA is profiled employing a few marker regions from the genome, and next, the lab uses its own pet genetic database to calculate probability—how common is this particular pattern in the wider population? In other words, how likely is it that this hair could have come from any other dog or cat than the one linking the criminal to the crime?

In the case of the triple homicide in Indiana, a representative of VGL testified that the statistical chance that the feces sample on the shooter’s sneaker and the feces in the yard of the scene of the crime came from two different dogs was staggeringly low. In fact, it was one in 10 billion. And since there aren’t even close to 10 billion dogs in the entire country that meant the feces on the sneaker and the feces in the yard came from the same dog.

The VGL has so much DNA to compare samples to because they’ve accumulated it through other work they do for breeders and pet owners—looking for inherited disease in breeding animals, or checking parentage. The DNA of millions of cats, dogs, horses, cows, elk, bear, wolves, and other animals has been stockpiled.

The lab work, according to Wictum, takes two to four weeks and costs, on average, about $2,000.

For some prosecutors, that added expense strains the budget. And yet the analyzed evidence can be crucial, as a number of cases show.

An attempted sexual assault case in Iowa in 1999 was solved largely because of dog urine. Though the victim could not positively identify her assailant, her dog could—by having lifted his leg on the tire of the man’s truck. DNA matching of dog and tire urine placed the man at the scene of the crime.

In Kansas City, in 2009, a single cat hair from inside a victim’s pocket helped convict Henry Lee Polk of first-degree murder. Polk had nearly decapitated Stephen Nolte during a dispute over money. The victim’s pockets had been turned inside out and his money was missing. One cat hair from those pockets was linked through mitochondrial DNA testing to the cats at the suspect’s house.

And in the horrible and famous case of 7-year-old Danielle van Dam in San Diego in 2002, DNA testing determined that dog hair found in neighbor David Westerfield’s trailer matched that of the little girl’s pet Weimaraner. It was part of the evidence used to convict him of kidnapping and first-degree murder. He was sentenced to death.

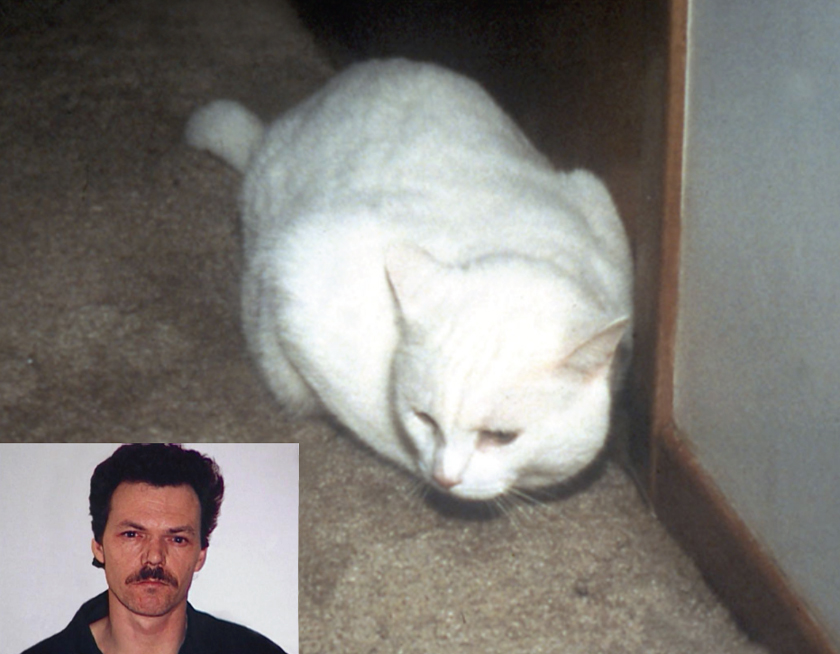

Though Wictum says that it’s dog hair her lab analyzes most often in crime cases, the very first case in which nonhuman DNA was presented as evidence in a murder trial involved a white cat called Snowball and a genetics scientist named Dr. Stephen J. O’Brien, then the chief of the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity at the National Cancer Institute, (who also happened to be an expert on cat genetics).

In 1994, 32-year-old Shirley Duguay, a resident of Prince Edward Island, Canada, vanished. It would turn out that she was dead, murdered by Douglas Beamish, her on-again-off-again common law husband. Initially there was little physical evidence to link him to the crime. But a plastic bag containing men’s sneakers and a jacket splattered with the victim’s blood was discovered. In that jacket, were a number of white cat hairs that looked to an investigator, Constable Roger Savoie, suspiciously similar to the white cat Snowball owned by the suspect. But getting a lab to process those hairs turned out to be a tough task.

“He immediately called the DNA forensics lab in Halifax and he said we need to type these hairs and get a DNA profile of the cat because I think I know who the cat was,” recalls Dr. O’Brien. But DNA forensic science was fairly new and animal DNA evidence was unheard of. Perhaps unsurprisingly, says Dr. O’Brien:

“There was a reaction of incredulity from the forensic people who said, ‘What are you talking about? This is a human DNA homicide operation. We don’t do cats or dogs or aardvarks or anything else. We just work on humans.’ And so Constable Savoie was very frustrated.”

Savoie searched for someone who could do the work, eventually contacting Dr. O’Brien, who in the course of researching cancer was “studying domestic cats as a model for whole bunch of human hereditary diseases.” O’Brien remembers Savoie’s desperation as he said, “Dr. O’Brien you’re my last hope…”

It was an odd partnership, but it worked. Dr. O’Brien and his lab team discovered usable DNA in the root of one of those cat hairs and it appeared to match exactly the DNA analyzed from Snowball’s blood. But he also analyzed the DNA of 20 neighborhood cats to be sure that inbreeding hadn’t resulted in a lot of similar DNA profiles among the population. It hadn’t.

At the trial in Summerside. Left to right: Victor David, Constable Roger Savoie Marilyn Raymond and Dr. Stephen O’Brien. Photo courtesy of Dr. Stephen O’Brien.

O’Brien and his team testified in court, Beamish was found guilty, sentenced to 18 years in prison, and veterinary forensics history was made.

From that one case, an entire field of science is growing.

Dr. Martha Smith-Blackmore has seen it firsthand. In 2008, she helped establish the International Veterinary Forensics Sciences Association (IVFSA), a group with 130 members in 16 countries.

“It’s still something of a nascent field,” says Dr. Smith. So much so that it wasn’t taught when she went to vet school in the 1990s. Instead, she learned it on the job, long before the term “veterinary forensics” was even in common use. Yet now, Dr. Smith is teaching the subject at the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University. It’s not only on the curriculum at many vet schools, but just last year, the University of Florida, and its Maples Center for Forensic Medicine, began offering a two-year master’s program in veterinary forensic sciences.

Dog and cat DNA database have been established in the United Kingdom over the last few years. And, here in the U.S., Wictum’s lab, VGL, created the “canine CODIS” (Combined DNA Index System) in 2010, which helps law enforcement battle criminal dog-fighting. This database, generated through a consortium of animal welfare groups, including the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, is used to discover connections among the people involved in dog fighting by identifying DNA and lineages in the dogs.

The field is so new that Dr. Martha Smith-Blackmore was doing veterinary forensic work before the term was commonly used.

As the field expands, it is providing ever more ways to solve crimes. The growth of veterinary forensics, says Dr. Smith, allows forensics veterinarians “to cross-pollinate with the anthropologists, and the forensic odontologists [experts in bite marks and other dental evidence], and the entomologists—so we’re sharing our science and learning from their science.”

Today, as it has been for decades, though, solving human crimes with animal evidence isn’t always about the DNA.

One of my favorite cases comes from 1985. According to the book “A Fly for the Prosecution: How Insect Evidence Helps Solve Crimes,” by forensic entomologist M. Lee Goff, the mangled body of a grasshopper, which was missing a hind leg, was collected as evidence from the clothing of a murder victim in Texas. When a suspect was searched, the hind leg of a grasshopper was found in the cuff of his pants. “The fracture marks matched perfectly,” Goff writes. And coupled with other evidence against him, the accused was convicted of murder.

2 Responses to “Pet CSI: How Dog And Cat DNA Nabs Bad Guys”

The Westerfield trial (in the van Dam case) was reportedly the first in the USA to admit canine DNA, and the first in California to admit mitochondrial DNA, for both human and dog identification. So, as in the Polk/Nolte case, the defendant was linked to the crime through mitochondrial DNA. But the statistical chance that the dog hair found in Westerfield’s motor home could have come from a dog other than Danielle’s Weimaraner, wasn’t only one in 10 billion as in the Stroud case, but was as high as one in 11 or 12. So there could have been another dog – even in that same neighborhood – which would also have matched.

Unlike the Stroud case, and the attempted sexual assault case in Iowa in 1999, there was no proof that defendant Westerfield had been present at the scene of the crime – in fact there were two widely different crime scenes (the kidnapping site and the body dump site), and no proof he had been present at either.

You rightly point out that most of us don’t need a crime scene investigator to tell us how hard it is to avoid all that animal fur. So it is relevant to point out that, in the van Dam case, because victim and defendant were close neighbors (just one house and a side road in between), and the victim and her family had visited him only about three days before she was kidnapped, they (Danielle and her family) would surely have deposited some of their dog’s hairs in his house, and maybe in his motor home also. Of all the cases you mention, this might be the only one in which there could be an innocent explanation for the presence of the animal evidence. It is also relevant in this context to point out that there were many other animal hairs in Westerfield’s motor home, but none were reported with Danielle’s body.

In the van Dam case, like the Duguay case, the victim’s blood was on the defendant’s jacket, but in the former case, unlike the latter, the blood consisted of just one small stain. And this stain was so faint that the dry cleaners didn’t see it, and apparently neither did the police until it had been in their custody for almost a week. There was also little physical evidence linking Westerfield to the crime, and not just initially (as in the Duguay case) but even after his (Westerfield’s) trial and conviction. In fact, I think it would be more accurate to say there was NO physical evidence linking him to the crime, only some evidence linking Danielle to his home and motor home, and that evidence could have an innocent explanation.

I’m surprised to learn that the DNA of “millions” of animals has been stockpiled, as there were only 358 dogs in the database Joy Halverson used in the van Dam case in 2002. I’m pleased to learn that Wictum’s lab, VGL, created the “canine CODIS” (Combined DNA Index System) in 2010. Unknown blood was found in Danielle’s bedroom (which was the kidnapping site), and an unknown hair under her body yet, astonishingly – and inexcusably – the police didn’t use the human CODIS to try to identify any of it.

I’m pleased you mention forensic entomology. There is a saying: people lie but insects don’t lie. So you can trust entomology evidence. This science played an important role in the van Dam case. The entomology evidence pointed strongly to Danielle’s body only having been dumped two weeks after she was kidnapped. This was long after Westerfield was placed under police surveillance, giving him a strong alibi. M. Lee Goff was one of the four entomologists who testified at Westerfield’s trial. He was hired by the prosecution, but even he gave a date which excluded Westerfield

Wonderful job writing Pet CSI: How Dog And Cat DNA Nabs Bad Guys |

WBUR’s The Wild Life.

Comments are closed.