Here’s A Debate: Can Chimps ‘Say’ Apple?

When “Dutch†chimps living with “Scottish†chimps modify the way they call for apples, what does that tell us about human language?

By Vicki Croke

A new study has shown that chimpanzees may possess some of the building blocks of language after all, something scientists have hotly debated for years (and will continue to, apparently). And it all came from a study involving “Dutch†chimps, “Scottish†chimps, and the way they communicated with one another over the issue of apples when they met.

Vicki joins Here & Now’s Jeremy Hobson to explain what chimps may have to teach us about the evolution of human language.

Starting in 2010, researchers from the University of York and the University of Zurich took advantage of a unique opportunity to set up a study when nine chimps from a Netherlands Zoo were transferred to a zoo in Scotland with its own group of nine chimps.

No matter where they live, chimpanzees use specific calls to identify particular objects—a predator, for instance, or the discovery of a food source. These “referential calls†can communicate important information to other members of the group who then react appropriately—rushing away from news of a predator, running in toward a food call. And chimps can have distinct grunts for different types of food. Researcher Sally Boysen found that out when she worked on chimp cognition studies at Ohio State University. She was sitting in her office one day while the chimps were being fed by an assistant nearby. Boysen could hear the chimps vocalizing, and even though she couldn’t see them, and she had no information about their menu that day, she knew they were eating grapes. She realized then that over time she had come to understand some of the referential calls of her study group.

These kinds of chimpanzee referential calls are intriguing on many levels.

Scientists have thought these calls were innate and “fixed,†that is, that the calls themselves don’t have any flexibility and can’t be changed or modified. That is very much unlike words in the human language, which obviously have lots of flexibility and get modified all the time. And this is an important point, because it’s been argued that this apparent lack of flexible control over the referential calls is a deal-breaker when it comes to language—an essential way in which chimp vocalizations differ from human language.

So a group of researchers from the University of York and the University of Zurich wanted to investigate this and they had the perfect opportunity to test it out in 2010, when a group of nine chimps from a zoo in the Netherlands was transferred to a zoo in Scotland with its own group of nine chimps.

Before the move, the Dutch zoo chimps used a series of high-pitched grunts to identify apples, a favored food, and the Scottish chimps made low-pitched grunts for the same fruit.

What would happen when they met?

Well, nothing at first. But once the Dutch chimps bonded with the Scottish chimps, they started to sound like them. At least in their apple grunts.

Listen here: The chimp named Frek calling for apples before being integrated with the “Scottish†chimps:

And after bonding with the host chimps:

This may sound like a small development, but the researchers, whose study was published in Current Biology, have shown that these kinds of calls aren’t as “fixed†as scientists had thought previously. The calls are not just some sort of unchangeable emotional outburst. In fact, chimp referential calls are at least a little bit like human words in that they can be modified.

One of the paper’s authors, Simon Townsend, told me by phone from Zurich that “what we’ve shown with these chimpanzee food grunts… [is that] there seems to be some degree of control that they have over the production of these calls in the acoustic structure which basically brings these calls a little bit closer to the kinds of referential words we see in human language.â€

Townsend, a comparative biologist, is particularly interested in better understanding the evolution of human language. And this study appears to shed light on the evolutionary timeline of language. “Even though it’s not the same as what we see in humans—and we’re not trying to argue it’s the same—it still helps us better understand potentially at what point in our evolutionary history these kinds of basic abilities started to emerge.â€

According to Science Daily:

Given the relatively short evolutionary distance between humans and chimpanzees–five to seven million years—[the study] also suggests that our most recent common ancestor with chimpanzees also shared this “building block” of language.

Does it mean that another trait thought exclusively human has been discovered in an animal?

According to Smithsonian.com the answer is yes:

It’s an exciting development for some studying chimpanzee communication, because it implies that the primates have the ability to learn different tones for different objects—a kind of bilingualism that only humans were previously thought capable of. Earlier ideas about chimpanzee vocalization assumed that, unlike humans who can easily adapt to new languages, “chimp words for objects are fixed because they result from excited, involuntary outbursts,†Andy Coghlan writes for New Scientist.

In the scientific and academic battle over whether only humans use true language (with rules of syntax and grammar), the way we describe this discovery can be the equivalent of fighting words. Or grunts.

Studies involving apes and language have always fascinated me. Whether we think of what these animals do as language or simply communication (and I’m certain there’s more to be discovered in this area—remember—there was a time when we thought animals weren’t capable of using tools or recognizing themselves in a mirror, chimps, among others have upended those notions), these studies provide some incredible insights into the minds and emotions of chimps.

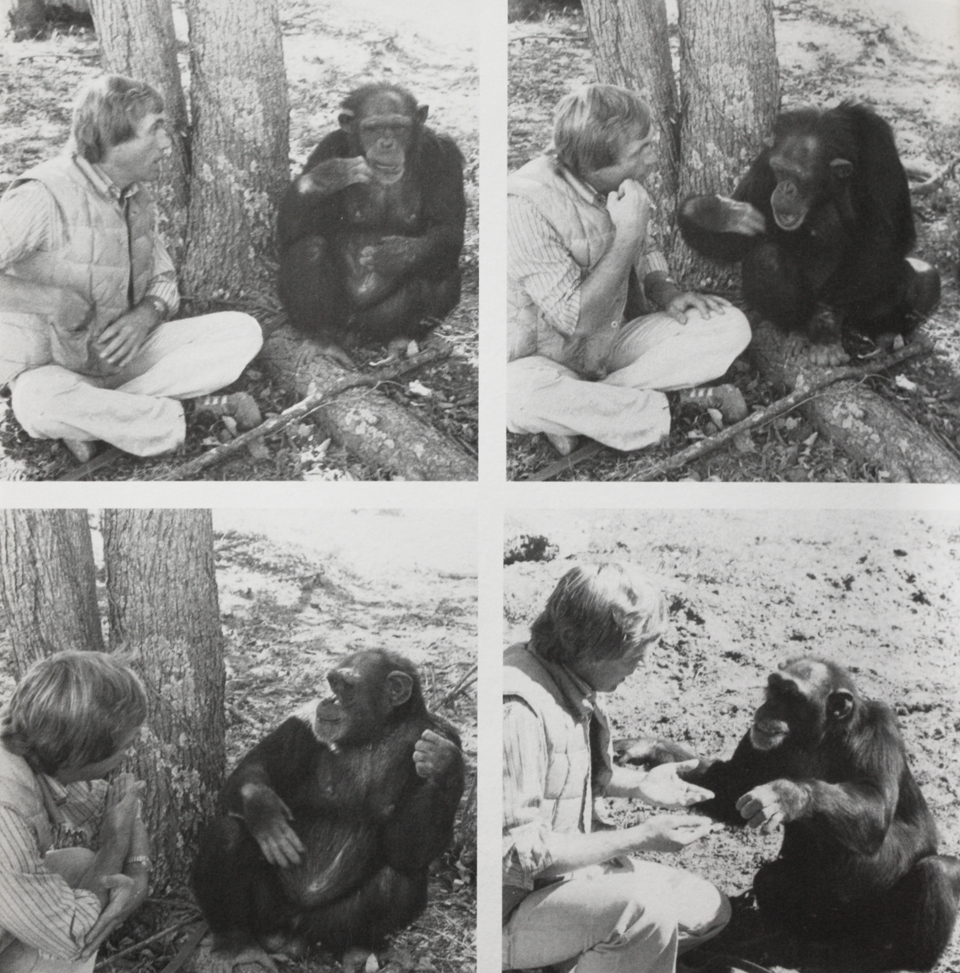

Take, for example, Washoe—she was the first chimp to be taught to use American Sign Language— at the University of Nevada starting in the mid-1960s. Her story is told in detail by Roger Fouts (her teacher and great champion) in his moving and insightful book, “Next of Kin.â€

TOP LEFT: Washoe signs “FRUIT.” TOP RIGHT: Roger responds “FRUIT” as Washoe reaches for some. BOTTOM LEFT: Roger asks pregnant Washoe “WHERE BABY?” and she points to her belly. BOTTOM RIGHT: Washoe is ready to head home, and she signs “GO.” Photos courtesy of William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York.

Washoe was being schooled and potty trained at the same time, and would run to the bathroom, signing to herself: “Hurry!â€

She was obviously smart, and her vocabulary eventually grew to hundreds of words. She would later even teach some signs to a young chimp.

Also, during a fight between two young males, Fouts observed that one of them broke off the action momentarily to turn to the dominant female and sign — “Good good me.”

Whether chimp communication makes the threshold of language or not, the chimps in these studies have been creative with what they’ve been taught.

Washoe, and other signing chimps, often combined words when confronting things they had no specific word for. So a swan became “water birdâ€; watermelon, drink fruit; a radish, hurt-cry food; and an Alka-Seltzer, a “listen drink.â€

These studies weren’t great for the “chimpness†of these chimps, many of whom were raised by humans. The apes often got a little confused about their own identity and place in the world.

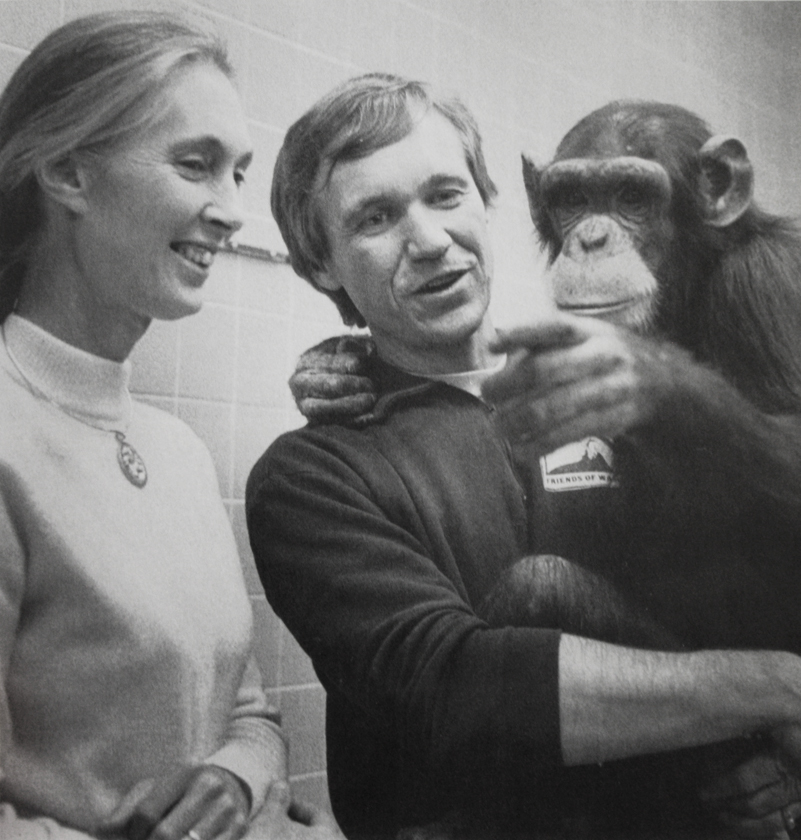

One chimp, Lucy, would leaf through the pages of Playgirl magazine at certain points in her estrous cycle, and she actually mixed a gin and tonic for a visitor. I know that story because the visitor—Jane Goodall—told me about it herself.

Jane Goodall with Roger Fouts and Tatu in 1983. Photo courtesy of William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York.

Then there was Viki, a home-reared chimp who was once asked to sort photographs of humans and animals into two piles. She had no problem placing photos of chimps in the pile with horses and dogs, but she did get one wrong. That was the photo of herself, which she added to the pile with humans, including Dwight D. Eisenhower and Eleanor Roosevelt.

All that said, what’s the answer to the basic question, do chimps use words? Townsend says he does not apply the word “word†to how the chimps vocalize for apple.

“Basically, there are still a number of differences between the kind of words that we see in human language and the referential calls that we see in animals,†Townsend says. “And we still are not completely clear on the underlying cognitive mechanisms that drive the production of these sounds. And to avoid making too many active analogies to human words, we don’t call them words. We call them functionally referential calls because the function of the call is to refer to something external in the environment.â€

As Townsend told me, “Essentially, you could say that this kind of closes, a bit, the gap between the kind of reference that we see in humans and the reference that we see in animals. But, of course, there still are a number of extra differences that still really make human words stand out compared to the referential calls that we see in animals.â€

But is this more like a change in accent or a change in vocabulary?

“One of the things that we can’t really say at the moment is exactly that question,†Townsend told me.

One Response to “Here’s A Debate: Can Chimps ‘Say’ Apple?”

Maybe so but can you teach one to say nuclear?

Comments are closed.