Gravity-Defying Grizzlies

Leaping off cliffs to attack a helicopter or picnicking for weeks in a family reunion, modern grizzlies are shaking up their image.

By Vicki Croke

Taking macho to new heights, one grizzly, tanked up on testosterone, leaped from a hillside and almost caught a hovering helicopter that had been pursuing him. This undated photo shows a grizzly in action. The Associated Press.

Grizzly bears are complicated. And GPS tracking, DNA analysis, and good old-fashioned observation are revealing a more nuanced portrait of the animals, one that makes clear that these bears are full of surprises—both heart-stopping and heart-rending.

For starters, in the world of grizzly paternity, DNA studies are making the case that macho matters. Perfect examples can be found in “The Boss,” a grizzly in Banff National Park who literally eats other bears for breakfast, and in grizzly bear No. G53, a 550-pound bruiser nicknamed “Big Boy” who’s been known to fling himself off the side of cliffs and toward a pursuing helicopter.

Just this week, the Calgary Herald reported that bear experts had discovered something that interested them—The Boss, also known as grizzly bear No. 122, had sired five—a significant number—of the park’s recent young. The paternity was revealed in DNA testing of the park’s bears.

Grizzly No. 122, nicknamed “The Boss.” He has been observed in Banff National Park eating a black bear (though in this shot, it’s a moose he’s consuming). According to the Wildlife Conservation Society, grizzlies “usually chow on the small stuff: berries grasses, roots, bulbs, tubers, and insects.” Though in some places they hunt larger prey or catch salmon. Photo: Dan Ralfa/Parks Canada.

Gordon Stenhouse, who heads the grizzly bear program for the Foothills Research Institute in Alberta, Canada, is the biologist in the chopper that Big Boy was trying to chomp. Stenhouse wasn’t surprised by this finding at all. He says a lot more evidence, including long-term data, is showing just how productive in terms of breeding these big mature males are. It’s an important piece of information in managing populations of bears, says Stenhouse. After all, bears can live to be 30 years old, and some of the old dudes with worn-down teeth should not be viewed as expendable just when they are, perhaps, at their “most productive” and going about making their most important contribution to the larger population.

Grizzly researcher Gordon Stenhouse was in the helicopter that “Big Boy” tried to catch. But he’s also seen amazingly social behaviors among grizzlies that he compares to “family reunions.” Photo courtesy of Gordon Stenhouse.

Big Boy, who was 16 when last encountered, and who may still be alive and well, has shown researchers his supreme maleness in several ways.

The first was that helicopter incident a few years ago. “Bears are smart animals,” Stenhouse says, “and if you’ve caught them once with a helicopter, they know the sound of a helicopter. So the first time with a helicopter, it’s not too difficult. The second time is much more difficult. And the third time is just darn hard.” It was number three for Big Boy. The bear was hunting wild big horn sheep in snowy, open country when Stenhouse spotted him. “[Big Boy] hears the helicopter and he runs towards the trees,” Stenhouse recalls. The helicopter followed. “We’re going up and up to see where the trees are moving and we’re watching him and we’re hovering,” he says.

“—in bear’s habitat, you realize that you don’t know as much as you think you do.”

The biologist and pilot lost sight of the big bear, but continued to hover, now level with a cliff. They were scanning the terrain, when suddenly, framed by the helicopter’s window, they saw the bear very close. Too close—all muscle, claws, and teeth, “jumping out at you to try to get the skids.” The grizzly came within just a few feet of bringing the chopper down. Big Boy had “had enough of being chased by a helicopter,” Stenhouse says.

It wouldn’t be the first or last time the researcher had the sensation that “in bear’s habitat, you realize that you don’t know as much as you think you do.”

One of Banff’s most famous bears, Grizzly No. 64 (now deceased), with three cubs in May 2012. “The Boss,” Grizzly No. 122, is the father of the cubs. Photo courtesy of Jack Borno.

As for Big Boy’s reproductive prowess, it makes sense that aggressive bears would get the girls. “I would assume,” Stenhouse says, “that that sort of aggression would come out during the mating season when [Big Boy] might encounter a younger male bear and would just chase that bear off and then mate with a female.”

And, indeed, that proved true in testing. First of all, Big Boy turned out to have the highest level of testosterone of any bear whose blood they had analyzed, but also, Stenhouse points out, Big Boy “produced a lot of cubs with females inside [Jasper] National Park as well as outside.”

Grizzlies have a well-deserved reputation for toughness. They are formidable predators who can weigh more than a thousand pounds (though more typically under 800 pounds), knock down a moose with a paw swipe, toss rivals through the air, and run nearly as fast as a horse. They can stand seven feet tall on their hind legs.

Given all that, probably more surprising than the macho-mating data, are the field observations showing how tolerant these bears can be toward humans.

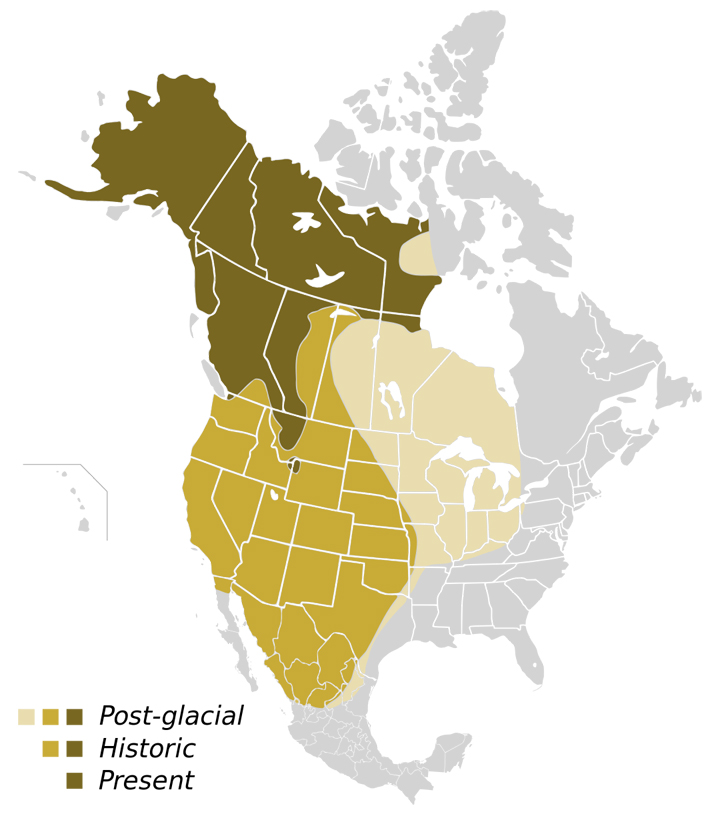

Shrinking distribution of the Grizzly Bear during post-glacial, historic and present time. From: Feldhamer, George A., Bruce C. Thompson, and Joseph A. Chapman. Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Cephas/Wikimedia Commons.

Stenhouse was tracking a collared bear by helicopter one rainy day, and he had a god’s-eye-view of a big male bear heading down a path directly toward some hikers. Since they couldn’t see each other yet, Stenhouse thought he’d have to intervene before there was trouble. But before he took action, he saw the bear depart the trail, “sit down on his haunches,” and watch as the unaware hikers walked right by.

I have written about John and the late Frank Craighead—the famous and much-respected twin brothers who conducted a groundbreaking 12-year study of grizzlies in Yellowstone National Park starting in 1959. They had many hair-raising encounters with the bears, but found that mostly the animals wanted to be left alone. Out in the field one day, Frank saw that seven huge grizzlies were running side by side straight at him, “like an onrushing train.” That’s about as scary as it gets. Yet when the bears caught his scent (grizzlies have relatively poor eyesight) they swerved away from him. One incredible sequence in a National Geographic documentary on the Craigheads, shows a mad scene when the brothers race to their red Ford station wagon to escape a darted bear waking up in a rage.

An incredible bit of historic footage: the Craighead brothers leaping for the safety of their red Ford stationwagon as a gladatorial grizzly wakes from sedation:

[youtube=https://youtu.be/-QCZY6eUWVA]

Stenhouse says, “Bears are tolerant of people for the most part. That doesn’t mean they’re not a dangerous animal. They can be. But people move by them all the time when they’re out in bear habitat.”

Stenhouse has been studying bears for decades—polar bears first, then grizzlies—“Trying to understand how the health of the bears relates to the environment in which they live, for example, we’re looking at forestry and oil and gas and mining activities—so we want to understand the health of the bears, not just how many there are.” He finds that the picture of grizzlies painted when he was in school—mostly solitary animals except for during the mating period—is a little out of focus. He’s seen too many behaviors, especially social ones, that don’t fit.

Grizzlies can be almost gregarious, and even friendly or loving toward other grizzlies, especially relatives.

Grizzly bear researcher and PhD candidate Sarah Elmeligi, working out of Banff National Park, says she has witnessed all kinds of unexpected social behavior among grizzlies—including “play dates.” In one case, she observed two females, each with three cubs, together in a grassy open area by the mouth of creek. “It’s not like the moms are sitting back and drinking tea and watching their kids on the monkey bars,” she says, but they did hang out on “multiple occasions.” In part, it likely provided safety from males who can kill cubs during mating season, but, Elmeligi says, “It really demonstrates that grizzly bears are so much more social than we give them credit for and that there are occasions where they’re not just simply tolerating each other because there’s a lot of food around, but there are actually occasions where they are spending time together.”

Sleepy bear: Grizzly bear No. 122, “The Boss,” is one of Banff National Park’s most famous residents. Photo: Parks Canada.

Stenhouse agrees. He fondly remembers one July observing three adult females—two sisters, and the grown daughter of one of them, each with their own cubs born that year. “They all got together—all those three adult females on the side of a mountain and spent about two weeks moving around together,” Stenhouse recalls. They fed as a group and slept close to one another in the same area. “You know, in humans,” Stenhouse says, “we think of a family reunion in the summer where we might get together at a cottage or somewhere like that with different generations? We had no idea that grizzly bears actually do something that I think is quite similar to that. We had no idea that that occurs.”

These new observations reveal, he says, just how careful we humans need to be when managing grizzly populations. There’s still so much we don’t know about their social structure.

Ultimately, when Stenhouse sizes up these big, formidable predators, he says they are surprisingly tolerant. And that they are animals who could use some tolerance in return. “I guess the final message for people is that bears can do pretty well if we don’t kill them. Poaching events are still a big issue. Illegal killing. Bears basically share their landscape with us so if we were a little more educated and tolerant of what they have to offer us… I think we really can co-exist.”