Take The Bat Man, Dracula, And Tequila. Mix Well.

How a famous biologist spent his career saving ‘the tequila bat’ and rectifying the image drawn in Bram Stoker’s classic story.

By Vicki Croke

On the nights that the teenage Rodrigo Medellin didn’t have enough cow’s blood stored in the freezer’s ice-cube trays to feed the 10 pet vampire bats he kept in the bathroom, his sister would help him draw some of the life-giving fluid from his own veins. Then, from behind the bathroom door, the winged mammals would stir with anticipation, recognizing his approach. When he walked in the room, he remembers, the bats “were ready.”

No wonder he grew up loving Bram Stoker’s classic horror story “Dracula.” And, no wonder he would become known as “The Bat Man of Mexico,” the high-achieving, much–honored conservationist who has saved bats, and, in so doing, has also ended up helping Mexico’s most famous export—tequila, which depends on those pollinating mammals.

One of the biggest tasks for Medellin and his students: making bats known to the people who live near them. Photo: Rodrigo Medellin.

We caught up with the 57-year-old biologist at the New England Aquarium, which was screening the wonderful David Attenborough/BBC film about Medellin and his work: “Natural World: The Bat Man of Mexico.”

Medellin, dressed in a black sweater and black slacks, is as irresistible and hypnotic as that gothic Transylvanian Count, though minus the suave creepiness.

Medellin was already a mammal-obsessed 11-year-old kid who, in the late 1960s, landed a stint on a Mexican TV quiz show called “The 64,000 Peso Challenge.” The first young student to do so. He didn’t win the top prize, but over several appearances, his astounding knowledge about animals drew the attention of a dean at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City, where he now teaches.

Medellin was bat obsessed starting in his teens. His parents–a Wagnerian opera singing mother and an accountant dad who owned an ice cream factory, always supported his passions. Photo: Rodrigo Medellin.

The dean invited him on field expeditions, and members of the department put the first bat into his hands when he was 12. He was hooked. “That blew my mind away,” he says.

The diversity of species amazed him—the variety of shapes, sizes, natural histories, diets. There are 138 species of bat in Mexico and he got to know almost all of them, though he he did specialize in one kind of bat—the lesser long-nosed bat, sometimes called the tequila bat.

They were considered plentiful, but almost 30 years ago, as Medellin traveled to survey them, he found their caves to be barely occupied and even empty of them. For years, people, not understanding the important role of bats, had been burning and even dynamiting the caves they roost in—often because they mistakenly thought they were killing vampire bats.

The population crashed and the species was designated as threatened in 1994. Trouble for the bats meant trouble too for the country’s famous drink—tequila. As it turns out, the agave plant, from which tequila is made, depends on the lesser long-nosed bat for pollination. Migrating bats pollinate the plants once a year as they feed off them during their long migration up the West Coast of Mexico along their “nectar corridor.”

Medellin worked with the government to identify and protect a network of these caves, keeping the bats safe—and in fact, increasing the number of colonies.

A big part of the effort was education. Medellin has always wanted everyone to see bats as he does.

It can be a tough sell. Bats have been loathed across many eras and cultures—symbols of the Underworld, synonymous with witchcraft. On this continent, before the entrance of Europeans, Medellin says, bats were associated with the harvest, abundance, and with good things.

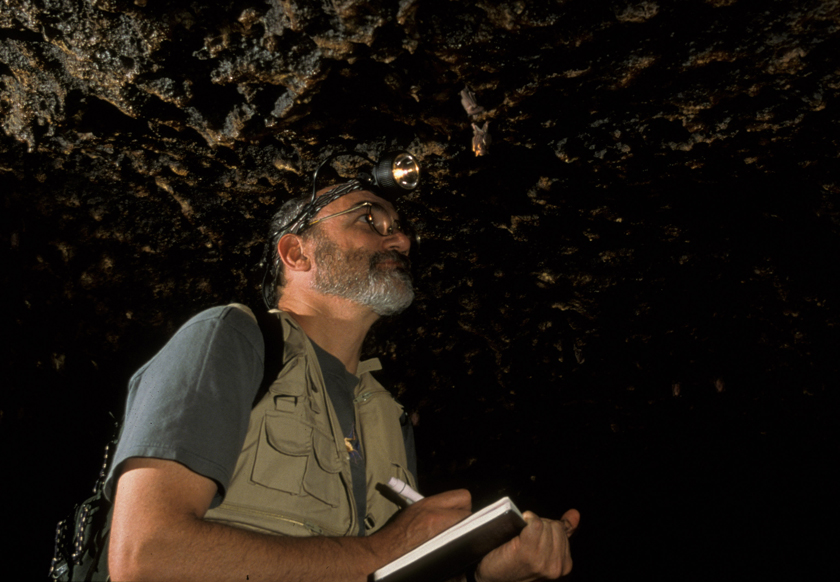

Medellin has worked for decades to keep bat caves safe. Photo: Program for the Conservation of Mexican Bats.

But in 1897, Stoker’s horror story of an evil vampire able to shape-shift into a bat that targeted innocent virgins helped cement a sinister image for bats. “That is what really caused the catastrophic decline in the image of bats in the minds of people. From that moment on, bats are evil, bats are dirty, they bring you disease…bats are no good. So my entire career has been spent trying to counter that negative image.”

And yet for the good-natured Medellin, there are no hard feelings: “I absolutely love the book! I love the book. I REALLY like it,” he says, laughing. He’s drawn to “the love story beyond time,” and jokes that maybe he needs “a shrink” because he is “hypnotized by Renfield, the madman in the prison that Dracula communicates with.” But the book has given him work to do. “I’m not anti-Dracula, or anti Bram Stoker at all,” Medellin says, “it just happens that it’s an accident of literature that he used a model that is affecting my professional practice and therefore I have to spend a long time trying to counter what he said.”

The membrane of a bat wing employs a network of delicate muscles in flight. Photo: EOL Learning and Education Group/Ari Daniel Shapiro.

A shame especially for a species that is so much more hero than villain. So much of our human lifestyle is dependent on their gifts.

Just a few highlights from the bat resume: Bats gobble up harmful insects, eating nearly their own weight in mosquitoes nightly, for instance. Or consider the Mexican free-tailed bats—one million of these bats can consume ten tons of crop-raiding moths in a single night. Bats disperse seeds (outshining birds), and they pollinate flowers. They are vital to whole ecosystems and to the agricultural industry. Around the world, tropical forests depend on them. In some places, they are responsible for 95 percent of the forest regrowth.

Millions of bats gobble up tons of insects every night. Photo: Program for the Conservation of Mexican Bats.

In bats, Medellin says he has found professional and personal nirvana. He is a much-esteemed professor of ecology, has received prestigious awards like the Whitley, and has been introduced to audiences by the likes of Britain’s Princess Anne. Most of all, it is in the reeking, cockroach-infested guano pools of bat caves, though, that he finds a kind of peace that touches his soul.

In one scene in the documentary, he rubs the guano-rich dirt of the floor of a bat cave between his fingers, looks into the camera, and declares that it makes him feel so serene, he could lie down and take a nap.

Steeped in his element: No matter what the conditions, The Bat Man loves the caves. Photo: Rodrigo Medellin.

David Attenborough says, “Rodrigo knows guano.”

He also, obviously knows bats. It’s a knowledge that has deepened over time.

In fact, for Medellin, life has come full circle. He’s not keeping bats in the bathroom anymore, but he is helping to keep them in the caves where they can now safely roost. His study species, the lesser long-nosed bats have recovered so completely that they are in the process of being de-listed in Mexico.

But if the lesser long-nosed bat has recovered, what’s next for Medellin? Well, everything. He’s fascinated by big horn sheep, by pronghorn antelope who are highly endangered in Mexico, certainly by the jaguar, and just now, he sounds like that teenager again as he describes a new bat project. This time it’s the woolly false vampire bat. A big bat that eats other bats and may have a social structure something like a wolf’s. It’s a natural for Medellin. And another homecoming in a way. Because this species is an old friend too. Back to that bathroom bat cave he had as a teenager. As it turns out, after the vampire bats moved out, it was a couple of woollies who moved in.

One Response to “Take The Bat Man, Dracula, And Tequila. Mix Well.”

I LOVE this guy! Thank you for bringing him and his subjects…to the light of day!

Comments are closed.