In a gabled Victorian house, perched on a hill overlooking Boston

Harbor in Dorchester, the day begins a little after six in the morning

with Bible study and prayer.

This building was once a crack house. Now, it is home to the Azuza

Christian Community Church and the Ella J. Baker House, which provides

an array of after school and youth outreach programs. It's led by

Pastor Eugene Rivers, a 51-year-old Pentecostal, who studied briefly

at Harvard and Yale, but moved here in the 1980's. That's when a

crack epidemic was raging in Boston, and a bright and outspoken

young drug dealer named Selvin Brown challenged the black churches.

Interview with Reverend Eugene Rivers

"So when the bullets fly, and all hell breaks loose... it's the faith that makes the difference."

Recorded in Harvard Square, Cambridge, by reporter

Anthony Brooks

|

|

|

Brown argued that the reason that a generation of very alienated

young black males held entire communities hostage was because

the black churches had failed to meet a generation on their own

turf.

Back then, Pastor Rivers, who had a penchant for controversy and

an appetite for publicity, took up the call and raged against

his fellow clergymen for ducking their duty. Later, in 1992, the

violence in Boston reached a dramatic climax during a funeral

service at the Morning Star Baptist Church. A gang of hooded men

stormed the church, fired their guns, and cornered one of the

mourners and stabbed him.

Rivers says the Morning Star incident was the "wake up

call to black churches" and an indictment. He recalls, "The

black churches had failed to take their message to the street.

And as a result the street brought its message into the church,

with poetic justice: you were indifferent to us. We will now mount

an assault against you."

Out of The Morning Star attack was born the Ten Point Coalition:

an alliance of Boston clergy committed to ending youth violence

through programs of mentoring and collaboration with law enforcement.

Now, once a week, neighborhood clergy, police and juvenile justice

officials come together at the Baker House. They share coffee

and juice and swap information about potential trouble: who's

out of prison and back on the streets, who's recruiting for gangs

and where.

According to Boston Police Captain Robert Dunford, the collaboration

with the city's black ministers represents an important shift

from the racially charged tension of a decade ago. Then, a meeting

with Rivers would have been "confrontational," he says.

Now, they work together, and Dunford declares, "we cannot

do it alone."

At work is something called the one-in-ten rule. The clergy helps

police identify the relatively few seriously dangerous kids. In

return, the police leave the majority of the less violent ones

in the hands of the clergy. Over the past decade, crime rates

dropped in most American cities by as much as 50 percent. In Boston,

they plummeted by 80 percent, and there was a big drop in civilian

complaints against police. Captain Dunford is among many who say

the ministers played a critical role:

They're the most respected members of the

community, they have a lot of moral authority. When they speak,

even the hardened guy, he stops. I can't do that. I'm a white

police officer. The kid in the street isn't going to pay too much

attention to me. The most important factor is the legitimacy and

the credibility that they've given law enforcement efforts. The

black church is now the most viable institution in the black community.

Eugene Rivers says too many black neighborhoods are still dominated

by crack houses, liquor stores and broken down schools, which leaves

only the churches to fight for real social change. He says it is

because of his faith that he perseveres. His house was shot into

twice, and burglarized six times, he recalls, "but we stayed,

because of our faith. So when the bullets fly, and all hell breaks

loose, and none of the critics are around, it is the faith that

makes the difference."

On this particular, day there's talk of a new wave of car thefts

in one neighborhood, new guns showing up in another, and a spate

of gang fighting in another. It will fall to Andre Norman, a street

worker and the field organizer at the Baker House, to try to intervene

ahead of the police.

We'll go down now, and talk to the guys, as a method

of intervention. So we say, 'Okay, you don't need the police to

come down here, we're getting their heads up, we're coming to

talk to you saying, "Listen, we have some programs over here

for you, there is a whole coalition that is in place to help you,

we're just the front soldiers that come down here to tell you

that it's for real."'

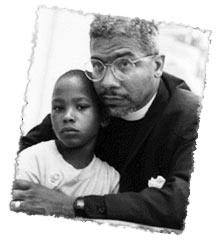

Andre Norman is 32. He served 14 years in jail for armed robbery

and attempted murder. He is now one of Rivers' most trusted lieutenants

and street workers. Today he's trying to help a fellow ex-offender

named Jay Rock, who is struggling with heroin addiction. Rock's

eyes are blood-shot and he looks much older than his 25 years.

He's been out of jail for two years, and says, like a lot of kids

back in the mid-nineties, he was lost in a world of drugs and

guns. At the time, he recalls, it was fun, "like the wild,

wild west."

He saw it as "a rush of adrenaline just knowing that somebody

is shooting at you and you're ducking bullets and running and

diving behind cars. That's what we deemed fun."

When he was 18, the fun stopped. Rock went to jail for armed

robbery and attempted murder and served five years. Now, he says,

he wants off the streets and the heroin. So he called Andre for

help.

There's nothing out there but death and jail, you

know what I mean. Me, I know I'm better than that. Obviously,

he knows I'm better than that, because he's willing to help me.

A few days later Andre Norman and a colleague head to the Community

Academy, a kind of last chance for kids who've been expelled from

public schools across the city. Norman makes weekly visits here,

as he does to jails, juvenile centers, and street corners. He calls it the last stop. "They either sink or swim. Well,

this is the sinking point, and a lot of these kids are going to

fall off and disappear."

Norman came to check up on a 16 year-old we'll call David whom

he first met in a juvenile detention center two months earlier.

David has been pulled out of the classroom for fighting, and he

warns him he could face expulsion. He says he can give David a

summer job if he can clean up his act.

Norman wears a small wooden cross around his neck. He tells about

a religious conversion he had in jail that saved his life. Although

he says he doesn't "hit people over the head with a Bible,"

his work is motivated by faith. "I don't have to go out and

scream 'God, God, God,'" he declares, "I live it, I

bring it, I've been taught it, and through what I've taught, I

share."

Eugene Rivers says ex-offenders like Norman, who have turned

their lives around, are powerful witnesses and examples of the

crucial role faith can offer a generation of young people lost

in urban America:

For someone like Andre, to know that he is loved

and forgiven, is very healing, it's redemptive, it facilitates

renewal, psychologically and culturally, and it gives my life

meaning - capital "M."

Inside, Baker House, the atmosphere isn't overtly religious.

There are no crosses on the walls, though staff and clients can

attend morning and evening prayers and Sunday services downstairs.

The Baker House operates its youth programs with a mix of private

and public money. Rivers is not among those who claim that religion

in and of itself saves these kids. But it is what compels him

to try to help them.

We recognized that there are a lot of young black

people, that they did not want to hear a religious message, they

wanted to see sacred institutions produce secular outcomes, which

would benefit the lives of young black people. It was then and

only then that the young people themselves initiated inquiries,

regarding the nature of our faith.

Because the government is committed to such"secular outcomes"

as literacy, job training, and mentoring, Rivers argues it's appropriate

that it support this kind of work with money. He didn't vote for

George W. Bush, but he says small black churches need financial

help, so he welcomes the President's plan. For Rivers, it isn't

about ideology. Like a lot of people, he's willing to combine

a bit of pragmatism with his religious fervor.

We are willing to judge the Republicans by their

works, and while we love the fact that the Democrats love the

good colored churches, rhetoric would be preferred to resources

at the end of the day… I'm amused that critics assume the colored people don't

have the intelligence and sophistication of the big white people.

Buckwheat, you need to stay on the plantation. Master Democrat

don't want you leaving his plantation to go over to Master Bush's

plantation.

At the Republican-sponsored faith-based summit in Washington

this past spring, speaker after speaker talked about how a closer

church-state collaboration would lift up communities in need.

Coalition Against Religious Discrimination

from a speech April 24th, 2001

|

Barry

Lynn

Executive Director of Americans

United for Separation of Church and State.

|

|

Welton

Gaddy

Executive Director of the Interfaith

Alliance.

|

|

Rabbi

Amy M. Schwartzman

Senior Rabbi at the Temple Rodef Shalom, Falls Church,

Virginia. |

|

|

The President has yet to convince key Congressional moderates

that this is a good idea. And with the Senate now in Democratic

hands, it's not clear what part of his program on faith-based

initiatives, if any, will become law. Whether or not the money

comes, the president's supporters in the faith community say his

effort has energized their work.

Those who have been pushing for government funding of religious-based

programs say the president's initiative is only the most recent

and it will not be the last. Those opposed, meanwhile, will continue

to warn that direct government funding of church programs not

only threatens individual freedom, but the vitality of the churches

themselves.

Welton Gaddy heads the Interfaith Alliance. He argues that if

the president and his allies really want to help the poor, they

should increase the budget for social programs, rather than just

divide the same pie into smaller pieces and pit congregations

against each other. Gaddy also worries that the Bush plan would

compromise the churches' ability to be the nation's conscience.

"When in the history of religion have you ever known a prophet

who would speak truth to power when the power was paying the salary?

That's where we are going with the government co-opting religion."

Others call the story of America a long history of government

and church working together. In his Notre Dame commencement speech

on May 20, 2001, President Bush called on the audience to "just

look around."

Public money already goes to groups like centers

for the homeless and on a larger scale to Catholic charities.

Do the critics really want to cut them off? Medicaid and Medicare

currently go to religious hospitals. Should this practice be ended?

Childcare vouchers for low-income families are redeemed every

day at houses of worship across America. Should this be prevented?

Government loans send countless students to religious colleges.

Should this be banned? Of course not.

The president's opponents don't dispute the extent to which church

and state are already entwined, but they say his plan would dramatically

alter a delicate balance. The debate will continue among politicians,

preachers, pundits, and activists of all kinds, one side calling

for the government to place our dollars where religious belief

can do good, the other trying to head off what it considers a

dangerous leap of faith.