Part I | Part II | Part III

First of three parts

Compiled by Ken George based on the

radio documentary by Michael Goldfarb

|

A family celebrating Passover. (AP)

|

Every year at Passover, Jews pray that they may celebrate the holiday "next year in Jerusalem." Since 1967, that prayer has been more than an aspiration. It has been something that any Jew could do. But celebrating Passover in Jerusalem comes at a heavy price.

|

A view of Jerusalem. (Av Harris)

|

Jerusalem is currently united under Israeli rule, but if there is to be a peace settlement in the Middle East, that status quo will have to change. So painful is that fact to Israelis and Palestinians that the problem of Jerusalem was put off to the end of the Oslo Peace Process. Now with that process in tatters, what is the possibility of negotiating the final status of Jerusalem? Will there ever be a possibility of praying in true peace in the Holy City?

For seven years - since the Oslo Agreement was signed - Palestinian and Israeli negotiators put off discussing Jerusalem. Last summer, the Jerusalem question burst into the foreground.

There's very little about Jerusalem that Israelis and Palestinians agree on, but one thing everyone acknowledges is that Friday is for prayer.

This year in Jerusalem, however, not everyone who wants to pray in the city can.

***

|

A Palestinian man shows his papers to an Israeli soldier at an army checkpoint on the southern edge of Jerusalem. (Av Harris)

|

At an army checkpoint on the southern edge of the city, soldiers climb onto a bus filled with elderly Palestinians from the suburbs - Palestinian Authority Territory. On three sides, Jerusalem's suburbs are under Palestinian control and in normal times this Friday journey would be routine. But these are not normal times. Since Ariel Sharon's stroll across the Temple Mount in September, a new Intifada has been underway. Escalating tension means that even these elderly folks are under suspicion.

The Palestinians are not allowed to pass and the bus they are on executes a wide U-turn and heads back towards Bethlehem.

Standing to the side, watching the scene are two women holding clipboards making notes on the soldiers activities, Roni Hammerman and Judit Keshet. "This is our local neighborhood checkpoint. Wherever you live in Jerusalem, there is a checkpoint near you," says Keshet. The two, monitoring their own soldiers for potential human rights violations, are members of one of the loneliest organizations in Israel at the moment: Bat Shalom, a Jewish women's peace group.

"Checkpoints have a lot less to do with security then they do with a show of force and I think they are absolutely counterproductive," Keshet says.

From the point of view of cooling down Palestinian anger the checkpoints do seem counterproductive.

***

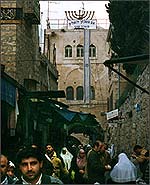

|

Palestinians enter the Damascus Gate.

(Av Harris)

|

This Friday, walking down the steep stone steps to the Damascus Gate, the main entryway from the Arab side of town into the Old City, a sullen anger steams off the crowd. The Palestinians here are Jerusalem residents.

Thirty percent of Jerusalem's population is Palestinian living primarily on the East side of the city in the area around the Old City. They came under Israel's authority after the 1967 war - when the Israeli Army took control of the whole city. Some of the Palestinians hold Israeli citizenship and all have a Jerusalem identification card, which gives them the right to remain inside Israel's borders.

All activity is under the eyes of Israeli soldiers standing in small groups or singly on the rooftops. The Old City's streets are narrow. A few people standing abreast loom large. The Palestinians instinctively avoid eye contact with the soldiers. With their eyes hidden behind wrap-around sunglasses, it is impossible to tell who the soldiers are making eye contact with.

|

Jamal abu Khadeja.

(Av Harris)

|

At the Damascus Gate I met up with Jamal abu Khadeja, a translator who works for the Palestinian Legislative Council. We walked towards what Jews call the Temple Mount - what Muslims call the Haram al Sharif, site of the Great Mosques: the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa. For Jamal, Israeli soldiers have been a constant presence in his life for 35 years. "I saw the defeat in the 1967 war... it's really hard," Awad says.."

|

Ariel Sharon's house which is located in the Muslim Quarter of the Old City.

(Av Harris)

|

From the Damascus Gate, we followed the crowd filtering down Al Wad street, toward the Haram where we passed under an archway on top of which sits the house Ariel Sharon bought in this quarter, the Muslim quarter. Rising to his windows from Islamic book shops along the row came music - songs celebrating the martyrs of the current Intifada.

I left Jamal at the entrance to the Haram. The Muslim authorities are not allowing non-Muslims to visit the place while Israelis are preventing Arab worshipers from coming to Jerusalem.

|

Palestinian market after Friday prayers. (Av Harris)

|

After prayers the mood in the street is noticeably lighter. Friday is for praying in Jerusalem but it is also for shopping. In a frenzy, people pick through piles of everything from vegetables, to underwear, to AA batteries before returning home to complete their day of rest.

In unpicking the problem of Jerusalem's final status it's important to separate out the question of the Holy City from the city of ordinary people living mundane lives. Doing that throws clear focus on a deeper problem that must be solved before there is peace: property. That is, Palestinian property taken over by Israel in 1967 and even earlier, in the 1948 War of Independence. The Camp David summit fell apart because just as a solution to Jerusalem seemed to be within reach, the Palestinian negotiators insisted on the rights of Palestinian refugees to return to those properties.

***

|

Michael Goldfarb and Naif Salaimeh. (Av Harris)

|

Jerusalem is a city of Doppelgangers, and as the Friday crowds dwindled, a Palestinian man who bore a shocking resemblance to actor Ben Kingsley in the film Gandhi introduced himself. His name was Naif Salaimeh and property, not God, is what he wanted to talk about. He offered to take me on a walk through the Old City to show me his family's bakery over in the Jewish quarter. "We kept it open even though we are not making profits." An unprofitable bakery is the price to pay to maintain his family's presence in the city. "We are here from hundreds of years," he says.

We climbed toward the west side of the city, Naif stopping occasionally to talk to friends. He no longer lives in the Old City but moved after his family's eviction to an Arab neighborhood on the northern edge of town.

|

Michael Goldfarb and Naif Salaimeh in front of his families bakery which is located in the Jewish Quarter. (Av Harris)

|

We walked under an archway past a recently installed metal gate - the boundary between the Jewish and Muslim quarters. We came to a building that had recently been renovated, the white stone front buffed to a high sheen. Through an arched picture window we saw some classical sculptures - Naif's boyhood home is now a Jewish-owned antiquities shop selling what it claims are genuine statues from the Temple in Roman times. It stirs strong emotions when he looks through the window of his former home. " I feel hatred sometimes," he says.

We carried on through the Jewish quarter. When the various quarters were named it had little to do with ownership. It simply indicated which religion's shrines were in a given section of the city. Jews lived in the Muslim quarter and Muslims lived in the Christian and Jewish quarters.

Today, however, the names have taken on a sectarian meaning for the Old City's 33,000 residents. Muslims regard their quarter as belonging to them and the Jews want their quarter to be exclusively Jewish. So just after conquering the city in 1967 they began to buy up Arab properties in the Jewish quarter. Not everyone wanted to sell and Naif rejects compensation as part of any political settlement over the status of Jerusalem. "The Old City is not something you can sell or buy."

Naif Saleimeh knows the workings of Jerusalem's property laws better than most Palestinians.

Despite his emotional connection to the family property, Saleimeh is remarkably practical when it comes to talking about settling Jerusalem's future. This may be because he works in the municipal government's planning department as an engineer where his colleagues are mostly Jewish.

***

While Naif's family clings to their bakery, their last small property in the Jewish quarter, Jewish settlers are steadily moving into the Muslim quarter. In all, about a thousand Jews have moved there in recent years.

|

A Jewish home in the Muslim quarter displays the Israeli flag. (Av Harris)

|

Along Al-wad Street, you can spot the settler houses easily enough - there are armed private security guards at the front doors. They escort settlers from home to school and back. The Uzi-packing guards seem excessive since other Jews go up and down the street unescorted all the time.

Most of the settlers are part of the Ateret Cohanim group. They are Orthodox Jews and militant Zionists who regard themselves as "pioneers," reclaiming a Jewish presence in all parts of the Old City. According to their promotional literature, they brave "physical and security hardships," planting the Israeli flag in the Muslim quarter.

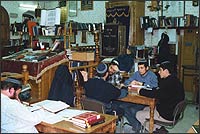

The life of the community is centered on education. Ateret Cohanim runs a "pre-military academy" to prepare students for their compulsory service in the Israeli army. There is also a traditional Yeshiva, where young men study in the way Orthodox Jews have studied since the first millennium - in an atmosphere that to an outsider seems utterly chaotic.

|

Inside the Ateret school.

(Av Harris)

|

In a room lined on three sides with bookshelves on the top floor of a building on Al Wad Street, 40 or so students of all ages are studying the Talmud. They are arranged around a dozen tables. Some study on their own, some study with Rabbis, others with partners. The lessons are varied; the learning goes on noisily and seemingly without order. I was beckoned by a young man with a light beard who was studying a lesson first noted 1,600 years ago. "During the time of the festival gatherings if you found money in the courtyards you weren't allowed to take it because it was holy money that was brought to the Temple Mount," he says. "Everything has to do with Jerusalem," he adds.

|

Natan El. (Av Harris)

|

The young man's name is

Natan El. His family emigrated from South Africa - "made aliyah" as it's called - in 1992. Natan joined the Ateret Cohanim Yeshiva 3 years ago and now lives in a dormitory down the street. He studies from 8:30 in the morning until 11 every night, with occasional breaks for liquid refreshment.

Natan offered us some tea. We went into an unheated room and Natan began to explain how he came to the yeshiva. "This is where everything unfolds." We are living prophecy here." And the thousands of Muslims that live in the city? According to Natan El, the prophecy isn't speaking about them.

Living on the floor beneath the yeshiva is a Palestinian family.

In 1948, when the Jordanians took over the Old City, they destroyed the yeshivas in the Muslim Quarter. But the Palestinian caretaker of this particular school kept its existence a secret.

In 1967, when the Israelis took control of the Old City, the caretaker presented the keys to the new authorities. The yeshiva restarted and, in gratitude, the caretaker's family was given the flat beneath where Natan and I were talking. That story doesn't deflect Natan from his prophetic vision of to whom the Old City will ultimately belong. For Natan El, the return of the Jews to Jerusalem is proof enough.

>> Part II

|

|