|

(Clarksdale,

MS) I love Mississippi. God alone knows why. It is just one

of those places I've visited that speaks to me. You probably have

places like that. You visit somewhere new on vacation or business

and something just strikes you to the core of your being that

makes you love the place. You go back home and scheme about how

to get back there. Well, I've been scheming to get back to Mississippi

for almost a decade. For "A Southern State of Mind," I finally

made it. (Clarksdale,

MS) I love Mississippi. God alone knows why. It is just one

of those places I've visited that speaks to me. You probably have

places like that. You visit somewhere new on vacation or business

and something just strikes you to the core of your being that

makes you love the place. You go back home and scheme about how

to get back there. Well, I've been scheming to get back to Mississippi

for almost a decade. For "A Southern State of Mind," I finally

made it.

On my previous and only trip to the state I had driven all around it for two weeks for the BBC World Service. My assignment was to "have experiences" and then write a series of "talks," BBC-speak for 15 minute essays with no tape, like the late Alistair Cook's "Letter From America." The journey was the most profound experience of America I have ever had.

The first place I visited was the Delta, hugging the Mississippi

River up in the northwest corner of the state. The Delta was created

by nature as the place where our history could be examined under

an open sky. The Delta is billiard table flat with cotton fields

stretching in all directions. At the western horizon is a low

bump: the levee holding back the bubbling, brown, turbid might

of the Big River. It is not an epic landscape by any means but

everything about the Delta is epic in its social extremes. The

poverty was epic. The view into American society was epic as well.

The

Delta is the epicenter of race in America. The worst of racial

oppression took place here. An historical marker along Mississippi

Highway 1 notes the location of Confederate war hero Nathan Bedford

Forrest's plantation. Forrest is better known for founding the

Ku Klux Klan. Emmett Till was murdered here -- and it is hard

not to see each tree as a potential hanging tree. But something

else happened here. Maybe because the Delta saw the worst of segregation

the people who survived it created the purest form of American

cultural expression: the blues. The Delta is also the place where

blacks and whites speak about race with a greater degree of honesty

than any place I've been to in our country. The

Delta is the epicenter of race in America. The worst of racial

oppression took place here. An historical marker along Mississippi

Highway 1 notes the location of Confederate war hero Nathan Bedford

Forrest's plantation. Forrest is better known for founding the

Ku Klux Klan. Emmett Till was murdered here -- and it is hard

not to see each tree as a potential hanging tree. But something

else happened here. Maybe because the Delta saw the worst of segregation

the people who survived it created the purest form of American

cultural expression: the blues. The Delta is also the place where

blacks and whites speak about race with a greater degree of honesty

than any place I've been to in our country.

I pulled into Clarksdale in 1995 already in a state of shock.

The drive down from Memphis on backroads had taken me to a place

called Marks which was the poorest place I had ever been in America,

worse even than the ghettos of New York during the 1970's and

Indian Reservations back in the 1960s. Marks was the poorest place

I'd ever been until I went to the next place down the road, and

then the next. These were hamlets that were so poor that I thought

I must be in the poorest country in Africa. Clarksdale is the

big town around here and I pulled off Highway 61 (yes, the same

one Bob Dylan was singing about) and headed downtown. I turned

down Issiquena Street, 150 yards of bars and juke joints, some

one story high, some two stories high. There wasn't a wall in

that whole stretch that was plumb straight, they all leaned out

of kilter and seemed on the verge of collapse but dozens of people

were wandering in and out. All black, all poor in a way that I

had never seen in America.

Under

the railroad tracks was a mid-20th century downtown completely

devoid of activity. Out on the highway, a new Wal-Mart had opened

killing the old shops dead. I walked into a record shop and found

myself talking to a lovely, heavily pregnant young woman. She

picked up from my accent that I was not from around these parts.

Neither was she. What do you think of this place? She asked. I

told her I was still coming to grips with the level of poverty

and so on. Then she asked aren't the people incredibly dark? Now,

I do not talk about race in this way so I was more than a little

taken aback. Adding to my discomfort was the fact that this young

woman was of mixed race herself. A white woman, who was obviously

her mother, was sitting behind her. But the young woman herself

had coffee-colored skin and African features. There was no way

to duck or dive around the direct question. I said, "These are

the most African looking African-Americans I have ever seen."

The young woman, her name was Selena, nodded in agreement and

went on to tell me what she had been told about this area, how

the segregation had been so absolute that the mixing down by the

slave quarters and after the end of slavery that went on in other

parts of the South didn't happen here. The African looks of the

slaves here had not been diluted. Anyway, that was her theory.

We whiled away an hour at the end of which she explained that

she was marrying the father of her imminent baby who owned the

record store the next night. I was invited if I was in town. Under

the railroad tracks was a mid-20th century downtown completely

devoid of activity. Out on the highway, a new Wal-Mart had opened

killing the old shops dead. I walked into a record shop and found

myself talking to a lovely, heavily pregnant young woman. She

picked up from my accent that I was not from around these parts.

Neither was she. What do you think of this place? She asked. I

told her I was still coming to grips with the level of poverty

and so on. Then she asked aren't the people incredibly dark? Now,

I do not talk about race in this way so I was more than a little

taken aback. Adding to my discomfort was the fact that this young

woman was of mixed race herself. A white woman, who was obviously

her mother, was sitting behind her. But the young woman herself

had coffee-colored skin and African features. There was no way

to duck or dive around the direct question. I said, "These are

the most African looking African-Americans I have ever seen."

The young woman, her name was Selena, nodded in agreement and

went on to tell me what she had been told about this area, how

the segregation had been so absolute that the mixing down by the

slave quarters and after the end of slavery that went on in other

parts of the South didn't happen here. The African looks of the

slaves here had not been diluted. Anyway, that was her theory.

We whiled away an hour at the end of which she explained that

she was marrying the father of her imminent baby who owned the

record store the next night. I was invited if I was in town.

It was a magical occasion. Jim O'Neill, husband and father-to-be

knew all the local musicians. After a lovely ceremony in a Victorian

mansion on the right side of the tracks we went to a juke joint

on the wrong side of the tracks overlooking the Sunflower River.

The place was a shack with no bandstand at one end and a tiny

bar that the other. The entertainment was extraordinary. A fife

and drum band played for a while, polyrhythms and shrieking melodies

that hadn't altered very much in the three and a half centuries

since they left Africa. Then we got the blues. And everybody got

up and danced. A fluid selection of local Delta bluesmen plugged

in and played. As there was no bandstand they wandered in and

out of the dancing couples. Shooting riffs at folks, urging the

dancers on.

The guests were an even mix of white folks and black folks and after a while, over a bit of bourbon, we all began to dance together. In this place, with its violent racial history whose residue was still warm to the touch in the extreme poverty around us, I found the contact extraordinary.

I

had many other adventures in Clarskdale and around Mississippi

and was glad when the assignment came up to go back to the South.

But I almost didn't make it to the Delta. It was a short trip,

just five days. My reporting began with couple of days in Georgia

starting on a Tuesday and I needed to be near Tupelo by Saturday

morning and I wanted to visit a couple of Civil War battlefields.

The focus of my piece was increasingly white Southerners, the

folks Howard Dean identified as people who should be brought back

into the Democratic fold. But after a night in Chattanooga and

a morning spent at Chickamauga National Battlefield, I booked

at top speed across Tennessee towards Clarksdale. I'll probably

regret it later. Southern Tennessee is beautiful and it might

have been nice to stay in a quiet place and maybe meet up with

some locals. But I felt a call. I drove from the rolling country

into the flat open to the sky landscape. The open space, the cotton

plants, dark green and just starting to bud stretched away to

the horizon. And I got misty-eyed. Some landscapes get you for

no reason. This one gets me. I

had many other adventures in Clarskdale and around Mississippi

and was glad when the assignment came up to go back to the South.

But I almost didn't make it to the Delta. It was a short trip,

just five days. My reporting began with couple of days in Georgia

starting on a Tuesday and I needed to be near Tupelo by Saturday

morning and I wanted to visit a couple of Civil War battlefields.

The focus of my piece was increasingly white Southerners, the

folks Howard Dean identified as people who should be brought back

into the Democratic fold. But after a night in Chattanooga and

a morning spent at Chickamauga National Battlefield, I booked

at top speed across Tennessee towards Clarksdale. I'll probably

regret it later. Southern Tennessee is beautiful and it might

have been nice to stay in a quiet place and maybe meet up with

some locals. But I felt a call. I drove from the rolling country

into the flat open to the sky landscape. The open space, the cotton

plants, dark green and just starting to bud stretched away to

the horizon. And I got misty-eyed. Some landscapes get you for

no reason. This one gets me.

Clarksdale

had changed for the better. The tilting juke joints on Issiquena

Street have been knocked down. There's a new place in town to

hear the blues: near the railroad tracks around the corner the

actor Morgan Freeman, a Delta native, has put some money back

into his community and opened a nice place called the Ground Zero

Blues Club. The one night I was in town I checked it out. Again,

the crowd was nicely mixed. Middle Class blacks from Memphis had

come down for some roots music. Halfway through the evening the

white country club crowd arrived, not quietly, either. Clarksdale

had changed for the better. The tilting juke joints on Issiquena

Street have been knocked down. There's a new place in town to

hear the blues: near the railroad tracks around the corner the

actor Morgan Freeman, a Delta native, has put some money back

into his community and opened a nice place called the Ground Zero

Blues Club. The one night I was in town I checked it out. Again,

the crowd was nicely mixed. Middle Class blacks from Memphis had

come down for some roots music. Halfway through the evening the

white country club crowd arrived, not quietly, either.

I drove around the area, listening to WROX, simply the best AM music station in the universe, to look for other changes. There were many improvements in the area. Habitats for Humanity had been around and many of the worst shotgun shacks had been replaced. I drove out to the levee and looked at the Mississippi, sluicing the detritus of the heartland down to the sea.

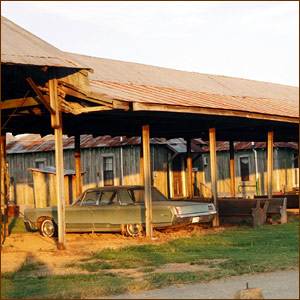

I went looking for Selena and Jim. They were gone. Moved back to her hometown of Kansas City. The record store is closed, as is the place where we had that most magical wedding party. I met some new folks. Bill Talbot runs one of the quirkiest hotels in America: The Shack Up Inn, just outside of town. It's on the grounds of the Hopson plantation. He's bought up half a dozen sharecroppers' shotgun shacks and moved them on the property. He's fixed them up with 1930's to 1950's knickknacks and turned them into little guest cottages, hence the name of the hotel: Shack Up Inn. The old field hands' commissary is a restaurant and bar. The massive old cotton gin has been turned into guest rooms as well.

I got up early the next day to drive clear across the state for work. As I pulled out of town, I drove past a sign for a little hamlet called Jonestown. I wanted to stop in but there was no time. Back in '95 I had stopped off there on my way out of town for an evening of Gospel music. Jonestown is an all black community. I was the only white person in the crowd of several hundred. The music was terrific and the last song had a simple chorus that has never left me. It pops into my head sometimes as a corrective to anxiety or depression. Or when I'm thinking about my country, as I watch it from over the ocean dividing deeper and deeper against itself. It's a simple phrase: "You don't know how blessed you are." But the Gospel choir repeated it over and over with different emphases and syncopation to make it seem like a sonnet.

"You don't know how blessed you are."

" You don't know howblessed you are."

"YOU don't KNOW how BLESSED you ARE."

"You don't KNOW... HOW ... BLESSED ... YOU ... ARE."

|