Published June 3, 2010

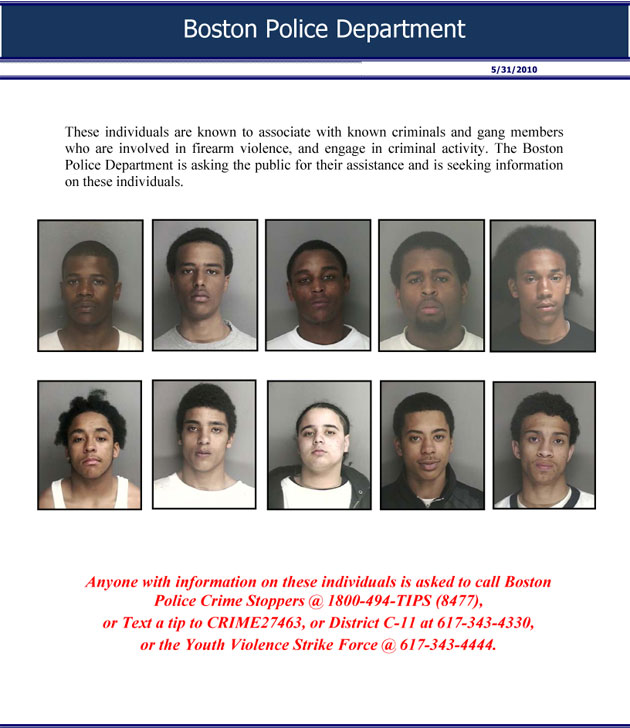

It looks like a wanted poster. Mug shots of young, black men with “Boston Police Department” printed on top. Underneath, in red text: “Anyone with information on these individuals is asked to call Boston Police Crime Stoppers.”

But none of the 10 men photographed is actually wanted for a crime. The intent of the flier is confusing.

I called Boston Police Department spokeswoman Elaine Driscoll today to explain.

“The Boston Police Department is hoping that if community members who are familiar with these individuals, that we know to be involved in violent activity — they are self-identified members of a violent street gang — we hope that the community will come forward, even in an anonymous way, with activity that they are involved in, because even an anonymous tip can lead to a successful investigation.”

The BPD has never done this before, and neither Driscoll nor anyone else I spoke with knows of it happening elsewhere.

On Wednesday, I raised the concern that the flier might infringe upon the alleged gang members’ constitutional rights.

I called Harvey Silverglate, a well-known First Amendment lawyer in Boston. He gasped when he saw the flier in the Globe yesterday. He’s outraged that more people aren’t, well, outraged about it.

“That strikes me as being some of kind of official defamation. And I was amazed that this use of the police power, which I consider to be an abuse of the police power, didn’t raise the roof somewhere,” Silverglate told me.

“And I think the reason is that there aren’t many people who are going to go out there and stand up for gang members or self-identified members even if there is no evidence that they’ve committed a crime.”

Silverglate thinks it could be a case of libel. It’s important to note that a printed statement is only libelous if it’s not true. In other words, you can’t sue someone for being embarrassed by something. But even if the flier doesn’t say something libelous, Silverglate says, it clearly suggests something libelous — that these people are wanted criminals.

There is no law against “being in a gang.” The First Amendment protects the right to free association, Silverglate says, provided there’s no collective goal to commit a crime. (That would be conspiracy.)

“But if the goal is simply to get together and organize a gang,” Silverglate says, “or as my son was in grade school, he and his friends organized what they called a posse, and it was perfectly lawful, because their goal was not to burn down the school. It was to have fun.”

[pullquote]”My son … and his friends organized what they called a posse, and it was perfectly lawful, because their goal was not to burn down the school. It was to have fun.”[/pullquote]

He says the flier reminds him of the laws in the old Soviet Union against hooliganism. It was a way for the government to arrest the unmentionables, the people they just didn’t like. He thinks this is a “smear campaign” against Boston’s unmentionables. (Silverglate wrote a book about vague criminal statutes, called “Three Felonies a Day: How the Feds Target the Innocent.”)

These young men may have a case, but they probably won’t sue. I talked to Carol Rose, executive director of the ACLU’s Massachusetts chapter, who told me gang members are easy to target because they’re not going to get a lot of sympathy and they’re not likely to fight back — not that that makes for good public policy, she said.

The burden is on the plaintiff to prove libel, and it’s doubtful that any of these young men would subject themselves to deposition and answer hours of tough questions about their past.

The issue of legality aside, what remains to be seen is whether this novel BPD tactic is effective. Part of the intent, according to police, is to shame these guys. But we already heard anecdotally that being pictured on the flier can be a badge of honor.

The other goal is to turn a newly vigilant community into a kind of citizen’s watch force. But Carol Rose of the ACLU told me the fliers might achieve the opposite of its intended effect — that it could make some people mistrust the police.

She says cops should stick to what they’re good at, building one-on-one connections in the community.

Boston police say this is but one of many tools used to fight gang violence. And those alleged gang members are known because of good old-fashioned police work.

Further reading: