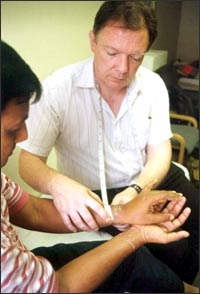

Dr John Joyce examines manacle wounds on wrists of Sri Lankan Tamils One way or another I have been working on this Torture story since that coup. I kept coming in contact with people who had been tortured. I didn't seek them out but the vaguely bohemian world I inhabited in Manhattan's East Village was a place of people in exile from the mainstream of the U.S., a natural place to find people in exile from violent oppression in their own countries. They came from Greece and Latin America, all were university educated middle-class people. Many were my age, people with whom I had much in common except this terrible experience. When you meet people who have been tortured it leaves you frozen in a sea of gelid empathy. You cannot take away that person's pain, you cannot share it with them. About the only thing you can do is bear witness and tell everyone you meet that in this place or that, this barbarity is going on. AND SOMETHING MUST BE DONE ABOUT IT.

I became aware of the work of the Medical Foundation for the Care of the Victims of Torture during the early 90's when survivors of the horrors in Bosnia began to arrive in the British capital. The local press wrote a number of features about the place. I decided I would do a story about the place. That would be my way of bearing witness. It only took me a decade to get around to doing it.

*In a perfect world my documentary would have been just the interviews with clients of the Medical Foundation edited into long monologues. In fact, for some Foundation clients, turning their terrible experiences into dramatic monologues is part of their treatment. Writing helps some people get control of their terrible memories. The young Rwandan woman whose testimony appears in the finished documentary is working on a play about her experience. Sadly, the reality of radio intruded into my grand plan to compel listeners to hear this testimony. All of the clients at the Medical Foundation speak English with very heavy accents and it would have been hard for the audience to stay with them. Then there were the silences. You can't have too much silence on radio. But in each interview there were long periods when my interviewee was lost for words. Even Luis Munoz, the Foundation's first client, more than a quarter of a century after his torture, lapsed into silence. In much of our conversation Luis told his story with a touch of irony and no sense of self-regard, even though his ability to endure the worst that Pinochet's torturers could do made him a bit of a hero to his fellow inmates. He has also had a very complicated love life, which he spoke about with rueful humor. He's an extremely charming guy. But sometimes all of that went away and he grew silent. What he was seeing in his mind's eye at those moments I don't want to guess.

*I sometimes wonder why the overthrow of the Allende government and its replacement with the Pinochet terror never inspired people to action in the way that Vietnam did. I've decided it has to do with the event's timing. The coup took place on September 11, 1973. In those pre-CNN days news could take a long time to filter out and about from some place as far away as Chile. There wasn't enough time for the story to build a head of steam because Chile was bounced from the news bulletins by a bigger event: the Yom Kippur War, which began three weeks later on October 6th.

October 1973 is for the post-World War II generation what August 1914 was for our grandparents. The Yom Kippur War triggered the Great Oil Price rise. Prices leapt 400%. This was the beginning of the great inflation, which effectively destroyed the bountiful economic world in which we practiced our political idealism. The cost of living rose vertiginously and the necessity of earning enough to keep pace with it made a lot of political ideals expendable. As political engagement faded, Chile's fate became unimportant. The moral censure that should have flowed from the streets of the U.S. towards Augusto Pinochet and his torturers never materialized.

*

After reporting this story I think there may be one other reason why so many people are silent about torture: its complex and shameful nature. According to Helen Bamber, the extraordinary 76-year-old woman who set up the Medical Foundation, "Torture is a dirty subject. It titillates." For more than a decade after the Chilean coup Latin America became a vast torture chamber, often with the connivance of U.S. governments. From Argentina to El Salvador and Guatemala tens of thousands were tortured and murdered. The nature of this brutalization as it was reported was almost always sexual. Men were castrated and their genitals shoved down their throats. Rape of course was endemic.

When Helen Bamber spoke of titillation I knew she was saying something that most people would prefer to be left unsaid. Torture is arguably the most immoral act committed by civilized people against their fellows yet somehow it doesn't galvanize us to action. If you're looking for an explanation of why, it could lie in how we respond to its sexually degrading nature.

*

I used to dream of being a filmmaker. One of the films I wanted to make was about a torture session. It would have been a short film made entirely from the point of view of the victim. It wouldn't have had the Guignol quality of Laurence Olivier applying a drill to Dustin Hoffman's teeth in Marathon Man. It would have been as close to reality as I could make it. The torturers would have come in and out of frame. The camera would have whipped from their faces to their hands attaching electrodes to the body. The frame would have gone white as the victim's blood pressure shot up when the electricity was applied and black when the victim fainted. The soundtrack would have been as distorted as the sound inside your head when this kind of violence is done to you. The viewer would be made as disoriented as the victim. My hope was to make people scream and force them to demand the end to torture.

I no longer dream of being a filmmaker. That career is for another life. I'm content with being a radio journalist. But I'd like to tell you what I was going to call that film: At Some Moment of Every Day, Someone, Somewhere in the World.

It is worth remembering that as you've read this diary or were listening to my documentary someone, somewhere in the world, was being tortured.

|