Grassroots movement: "We're fed

up!"

» Listen Almost, but not quite. Today Connecticut's Indians are again a force to be reckoned with, and non-Indians are again opposing them. A grassroots movement has taken root across Connecticut to roll back Indian sovereignty, power, and specifically, the right of tribes to build and operate casinos. Today Connecticut, the nation's third smallest state, is home to two of the world's largest casinos: the Mohegan Sun and Foxwoods of the Mashatuncket Pequots. Now, like a latter-day gold rush, the race is on for more. Attracted by the prospect of huge fortunes, at least five of the state's other tribes want their own casinos, which has galvanized casino opponents like Jeff Benedict. The boyish looking Benedict made opposition to Indian casinos the centerpiece of an unsuccessful run for Congress last fall. Now, as head of the Connecticut Alliance Against Casino Expansion, he portrays this effort as a grassroots David fighting the Goliath of Indian casino power. "This is a contest between the will of the people and the power of big money," proclaims Benedict, who adds, "We are fed up and we're not going to put up with anymore." They are stirring words, but putting the brakes on the race for more casinos is a challenge. The huge amounts of money involved, especially in Connecticut, will make it difficult to stuff the casino gambling genie back in its bottle. Money and Cultural Renaissance

The Mashantucket Pequots have built the largest gambling facility in the world, dwarfing anything in Las Vegas or Atlantic City: four cavernous casinos with 13,000 slot machines; and according to the tribe's brochure, 320,000 square feet of gambling space, which is roughly the size of 30 football fields. Ten years ago, this part of Connecticut was known for quiet towns and villages, half-way between New York and Boston. But it was a casino developer's dream, according to Robert DeSalvo, Foxwoods' Vice President of Marketing. DeSalvo, a non-Indian with an Atlantic City background, says more than 27 million people above the age of 21 live within a 200 mile radius of Foxwood, which gives the casino a huge population to draw from. "You couldn't pick it much better than this," he says. And the numbers explain why. Forty-thousand people flock to the acres of slot machines, roulette tables, and blackjack games every day, and their money pours into Foxwoods like water shot from a fire-hose; $125,000 dollars an hour; $3 million a day; $1.5 billion a year. This is huge wealth for a tiny tribe that had virtually disappeared until just a couple of decades ago. Michael Thomas, the tribal Chairman of the Mashantucket Pequots,

regards the huge and sudden wealth of this tribe as just recompense

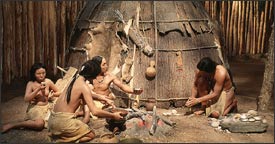

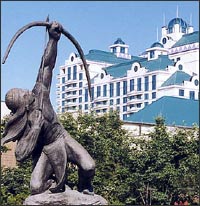

for centuries of mistreatment. "For us the wealth is not an end," says. "It's a means to an end." The casino fortune pays for the sprawling Pequot Museum, which tells the story of a once prosperous tribe and its fateful collision with Europeans. At the center of the museum is a detailed, life-sized recreation of a 16th century Pequot settlement. To the sounds of gurgling streams and singing birds, visitors stroll beneath a lush, green canopy of trees, past life-sized wax figures in traditional Indian costumes; it's a vision of a pre-colonial Eden - a world of wigwams and open fires; hunting and basket-weaving. Just a short walk takes you from the 16th century to the billion-dollar a year casino of the modern Pequot -- Las Vegas with an Indian accent: there's a huge crystal statue of a brave aiming an arrow skyward -- above the plastic trees; there are non-Indian croupiers and cocktail waitresses in stylized Indian outfits. It's difficult to resist the question, what does all this have to do with reclaiming a lost culture? It's a question that tribal spokesman Cedric Woods has heard many times and is getting tired of answering. Woods says the Pequot's huge wealth conflicts with the image that mainstream America expects of Native Americans, which is that they are poor, powerless and stoic, accepting their centuries of mistreatment as just part of being Indian. But the truth, declares Woods, is that "native people weren't poor and impoverished until they were colonized." Local Opposition: Jurisdiction is the Problem

Just a few miles from Foxwoods is the village of North Stonington, a small collection of wood-framed colonial houses with a mill pond in the village center. It is one of three towns that border the Pequot reservations, and for the past decade, it has been ground-zero in the local fight against Foxwoods and casino expansion in Connecticut. Since the casino opened in 1993, Nicholas Mullane, the town's first selectman, has watched the flow of cars and busses clog the winding, two-lane roads; he has complained bitterly that more police, emergency services, and road maintenance cost North Stonington an extra $600,000 a year, but because the casino is on a reservation, it pays no property taxes to the town. Mullane has a notebook 10 inches thick, stuffed with newspaper stories, editorials, and studies about the impact of the casinos on his town and the state, which he eagerly shares with a visitor. They chronicle everything from the inconvenience of increased traffic to alarming tales of bankruptcy, prostitution, suicides, and murder - all because of the casino, according to Mullane. "They call it a resort and casino," Mullane says with a sneer. "But it's a gambling hall and a bar." The Pequots argue that their wealth benefits the entire region: they say the casino pumps tens of millions of dollars a year into the economy and employees 11,000 non-Indians. And while Indian ventures are tax-free, the Pequots and the Mohegans, who run Connecticut's other casino, signed a deal with the state to hand over a quarter of their slot winnings, which adds up to a quarter of a billion dollars a year. This is true, but the funds are distributed across all of the state's cities and towns, leaving the three towns that border the Pequot reservation complaining that they are inadequately compensated for bearing the brunt of the impact. To date, there is little independent, empirical research on the impact of Indian casinos on surrounding communities. A Harvard University study concluded that tribal casinos generally benefit surrounding communities because most of them are located in poor, rural areas. But the study also noted that in more developed locations - like the Northeast - tribal casinos potentially prosper at the expense of off-reservation businesses. Opponents like Jeff Benedict say casinos only suck up disposable income - money that would otherwise be supporting movie theatres, shops, restaurants, all of which would pay taxes to Connecticut. "Money for casinos does not grow on trees," says Benedict. "It comes from people's pockets and it is not coming back out." Behind the growing opposition to tribal casinos in Connecticut is fear on the part of many citizens that they're losing control of their communities. As a federally recognized tribe, the Pequot reservation is regarded as a sovereign entity, exempt from local property taxes, state and local zoning rules or environmental laws. The tribe can also buy up land and add it to their reservation, which is what they've been doing -- all around the home of Sharon Wadecki, who lives in the neighboring town of Ledyard. Wadecki says she is concerned about jurisdiction. For example, when she has a problem with one of her Pequot neighbor's dogs, who does she call? Her local dog warden is powerless to do anything if the dog wanders back on to Pequot land. "For me jurisdiction has always been a problem," says Wadecki.

Wadecki is also concerned about the future. Because the reservation is beyond the reach of local and state zoning ordinances and environmental laws, the tribe could in theory swallow up Wadecki's world. "I could have a Ferris wheel next to me," says Wadecki with alarm. "They could build a toxic dump and no one could say anything about it." In fact, the tribe has no plans for a toxic dump, though it is

committed to expanding its reservation and to further enlarging

its casino and resort amenities. And why shouldn't it? After all,

any American corporation worth its salt would take advantage of

available loopholes and regulations to maximize its bottom line.

A point hammered home in the Pequot museum is that the tribe's wealth and power are not the result of "special privileges," but instead of the restoration of its sovereign status under federal law. Tribal Chairman Michael Thomas is dismissive of local residents who he says believed "the Indian problem had been solved." Thomas says he's committed to better relations with his non-Indian neighbors. But he says they must accept the tribe's right to exist and to prosper. And Thomas believes that people who are resistant to change are never going to accept what the Pequots have done, and what they have the right to do. "We represent the most feared change," says Thomas, "change that they can't control through their normal political process." » Next: Are They Really a Tribe?

|