|

Getting it Right » Listen

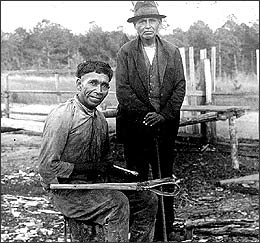

The controversy swirling around issues of tribal legitimacy and behemoth casinos in Connecticut obscures examples elsewhere of quiet success with tribal gambling. The Mississippi Band of the Choctaw Indians are a case in point. This past fall the tribe opened its second casino, the Golden Moon, in Philadelphia, Mississippi. It's smaller than the billion-dollar facilities in Connecticut. Still, the 9,000 members of the Choctaws clear $100 million a year and the casino represents the latest step in a stunning Indian renaissance. Two generations ago, the Choctaws were the poorest tribe in the poorest state in the nation. Fergus Bordewich, author of "Killing the White Man's Indian," spent time on the Choctaw reservation in the 1960s, when it was "a forgotten community; just a scattered collection of cabins and shacks in a depressing corner of the Mississippi backcountry." Bordewich recalls that the reservation's roads were unpaved, kids were unclothed, and most of the tribe was far removed from the world of money and jobs. John Hendrix, a non-Indian who works in the tribe's economic development

office, says at that time just 7 percent of the tribe had high school

educations; 86 percent earned less than $2,000 a year. "To

see where we are today," says Hendrix. "really paints

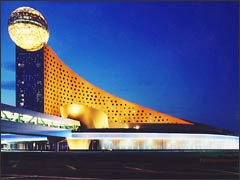

the picture of what has been done in a short amount of time." So Martin went to work. With the help of the Great Society Programs of the 1960s, the Choctaws built an industrial park and became the first Indian tribe to compete aggressively for low-skill manufacturing jobs, and it worked. They went into business with General Motors to assemble components for trucks and cars. More business followed: a factory that makes automobile speakers for Ford and Chrysler, a direct mail business and a construction firm, for-profit nursing care, a company that makes plastic knives and forks for MacDonald's, and since 1994 - casinos. Today the 9,000-member tribe is fully employed; in fact there's enough work for every member to have two jobs, and the tribe also provides thousands of jobs for non-Indians. Casino Wealth The Golden Moon casino is a long, curved orange edifice - topped

with an enormous glittering sphere that houses a restaurant and

lounge - and looks like a giant golf ball ready to tumble down onto the fountains below. If not beautiful, it is impressive. And

its amenities have brought something new to this once sleepy edge

of east Mississippi.

A few local residents from the town of Philadelphia complain about

the increased traffic and worry about being swallowed up by the

casino. But for the most part, the non-Indian community embraces

what the Choctaws and the man everybody here knows simply as "Chief"

are doing. They're grateful for the jobs and the economic vitality

it has brought to this county. David Vowell, who heads a local community

development group in town, says Chief Martin has always made an

effort to give back to the off-reservation community. "He's

offered to help with the local park, the local library," according

to Vowell, who adds, "People ask for money and he writes them

a check." This is a tribe with a casino, as opposed to a casino that defines a tribe. In the casino there are no tribal icons or other reminders that this is an Indian enterprise. The Choctaws say this is their business, not their culture. And the tribe's John Hendrix says the casino is just one part of a broad economic strategy that follows years of success with low wage, low profit enterprises. "It's important that we had that experience before the casino," says Hendrix. "When we got the revenue from the casino we knew how to use it."

The Choctaws don't get cash stipends; they are guaranteed jobs and college educations. And profits from the gambling is plowed back into other business ventures as well as tribal housing, schools and roads. "I look at it this way," says Chief Martin, "it's how you use the proceeds from the gaming, and I believe we're using them the right way." Not everybody across the state is a fan. For example Sam Begley, who represents Mississippi's non-Indian Gulf coast casinos, says it' unfair that the Choctaws don't pay state taxes. "We pay 12 percent of gross revenues in taxes, which is a disadvantage," he says. Begley says the Choctaws are having it both ways: on the one hand, he says, they are governmental and sovereign, but on the other, private and entrepreneurial. "There is a fairness issue," he says. "All businesses want to be treated the same." Begley accepts the idea that Indian tribes deserve a helping hand, but he argues that with advent of the Civil Rights act, the Fair Housing act, and the array of government assistance programs, there ought to be some way to break the back of racial disadvantage that stops short of giving special privileges and advantages to a particular group. "I would like to think," says Begley, "that the Choctaws want to be a part of our country." For their part, the Choctaws argue they don't pay state taxes because they don't get state services. The tribe pays for its own police and fire protection, court system, and roads. And Chief Martin says there's good reason that federal law protects reservations from the reach of state tax-collectors. "If there's something to be gotten from the Indian, [the states] usually get it." says Martin. "Congress was wise," he adds, "that the state would want to get its hands into the tribal coffer, and so it didn't allow that." New Wealth, Old Customs

The Choctaws are also using their casino wealth to preserve their native language, which is still widely spoken on the reservation by tribal elders. The fear of some on the reservations is that as this tribe becomes further integrated into mainstream American, the younger generations will lose their linguistic roots. Now, with the new wealth generated by the casino, Rossana Tubi-Niki has been able to establish a Choctaw language program. "In the past I've harped about the need for such a program," says Tubi-Niki, "but the problem has always been that we didn't have the money." Now the Choctaws do, so the language instruction begins in the reservation's Head Start program, where tribal elders like Lula May Lewis, introduces Choctaw to the tribe's youngest members. Speaking through an interpreter, Ms. Lewis says she cherishes the language and is happy to be ensuring that it lives on. On the day of my visit to the Head Start Center, a small boom-box

in the corner of the room was playing traditional Choctaw dance

songs. When I trained my microphone on it, Lula May Lewis approached

and began to sing along. It turned out that long before she became

a language teacher, she was a tribal singer. It was an interesting

moment: the modern boom-box in harmony with the tribal elder, which

prompted a discussion with Rossana Tubi-Niki and her assistant,

Jesse Ben, about the effect of all this wealth on the tribe; about

using casinos to preserve tribal traditions. As problems go, too much affluence is a pretty good one to have. And it's one that a generation ago no tribe in this country could even dream about. Contemporary Indian law is animated by the goal of restorative

justice; that the country owes something to Indian tribes as recompense

for its brutal policies of the past. But what does it owe? Economic

opportunity? Special rights? Casinos? The issue is complicated by

the collision of two powerful forces: the reach of Indian sovereignty

and the explosion of casino gambling across the country. Given the

corrosive power of money and politics, it's not surprising that

the idea of nations within nations has led to confrontation and

cynicism about Indian rights in places like Connecticut. But not

everywhere. The Mississippi Choctaws used their sovereign power,

including their casinos to pull themselves and many of their non-Indian

neighbors out of poverty and out of isolation from each other. Taken

together, these stories might point to a need for review and reform

of federal Indian policy; but they also demonstrate the benefits

of effective Indian leadership in America. |

Information

on Choctaw Language and Culture:

Information

on Choctaw Language and Culture: