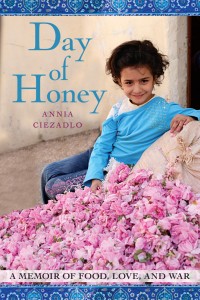

Photo: Courtesy of Simon and Schuster

It’s 2004 in Baghdad. The city is torn by war – a struggle that will end the lives of more ordinary citizens than soldiers or terrorists. And yet, somehow, families manage to wake up, run errands, go to work. Communities still gather around the dinner table. People take solace in their meals – but what do you eat when life seems more vulnerable than ever?

During the winter, food writers talk about “comfort food” so frequently that it’s become a cliché – but no cuisine deserves the title more than the food that families make together when their country is ravaged by war. Chicago native Annia Ciezadlo landed in Baghdad in the fall of 2003 to find a country relying more and more on warm and comforting homemade dishes. Moving between occupied Iraq to an increasingly violent Beirut, Ciezadlo tells a story of war from the vantage point of an ordinary kitchen table in her new book, Day of Honey.

Public Radio Kitchen talked to Ciezadlo on Wednesday about grape leaves, raw lamb and the beauty of everyday life in the midst of chaos.

PRK: I saw on your biography that you were born in Chicago. What drove you to move to the Middle East and report on culture there?

AC: Well, I was born in Chicago and then I moved around quite a bit, sort of lived in many different parts of the United States. I grew up in Bloomington, Indiana… I lived all over the U.S., anywhere from Ohio to Minneapolis, a summer in Portland, [in] Arizona… A lot of this is in the book, and I sort of try to make it clear how traveling all over the U.S. kind of shaped my view of the world, and it especially made me attracted to food, because food was always this thing I could count on, I could rely on, and it was always this thing that I knew to go to when I was in a new place.

If I moved somewhere new and I didn’t really know anything about the place, I would always try to find a restaurant or a market or just something that had anything to do with food – particularly street food – as a way to connect with the place and the people in it. Like one experience that really stands out is being in St. Louis and having barbecue with a woman who was selling barbecue on the street. Especially in cities like Kansas City and St. Louis, you get used to street food as a way to interact with people and have this human connection and feel like you know where you are.

So, to go to the Middle East – it’s funny, the story of the book is kind of, how did I end up the Middle East. I actually never intended to be a foreign correspondent, and certainly not in the Middle East. I basically met a guy (laughs) who was from Beirut and also happened to be – well, he was just a transportation reporter when I met him, but he ended up being appointed as the Middle East bureau chief for a newspaper. So you might say I was an accidental foreign correspondent (laughs). I definitely didn’t intend to be one.

PRK: So before you moved out there, did you have any background in Middle Eastern food? Did you know how to cook that style of food?

AC: It’s an interesting question, because I did without knowing it. I had always felt attracted to Middle Eastern food because my grandmother was Greek and so a lot of her signature dishes like grape leaves and vegetable casseroles and particularly lamb and vegetable stews are essentially very Middle Eastern, very very similar to food that you find in the Middle East, especially in home cooking.

PRK: Then did anything surprise you about the food you ate in Baghdad and Beirut?

AC: Oh, a lot of things surprised me (laughs)! I think the things that surprised me the most were what didn’t surprise me. I was always more surprised to see things similar to what I knew.

One of the greatest surprises of my life was tasting real Middle Eastern grape leaves and realizing they’re exactly the same flavor as what my grandmother used to make, more so than the grape leaves you get in a restaurant which are usually canned – I’m talking about the difference between the kind that have meat in them and the kind that just have rice. The kind that just have rice, the kind you might get in a deli or something like that, they’re usually from a can. And they have a completely different taste from the kind that somebody has hand-rolled and hand-stuffed and very lovingly made this stuffing and filled each one – you get a completely different flavor from that kind of thing.

PRK: I was reading an excerpt from your book online – the one where you eat raw lamb. How was that? Did that surprise you?

AC: That’s actually – it’s very similar to steak tartar, and it can be made with either beef or lamb In this case it was lamb, but it depends on what is freshest. It sounds crazy, but it’s actually not that unfamiliar if you’ve ever had steak tartar.

PRK: How was it? Is it something that is commonly eaten over there, or is it more special occasion food?

AC: I would call it a special occasion food – people eat it quite a bit, but it’s the kind of thing you only eat when you trust the person who’s making it (laughs). Because you don’t want to eat raw meat that’s been sitting out for a bit.

PRK: Can you tell me about Roaa, the woman in your book who, as your publisher’s summary puts it, “dreams of exploring the world, only to see her life under occupation become confined to the kitchen?”

AC: Sure – Rooa was my translator. We became very good friends, I stayed in touch with her over the years… she’s a big part of the book. I really connected with Roaa not only because she reminded me of myself – she’s about ten years younger than me – just as someone who wanted to explore the world and somebody who wanted to read everything in sight.

She’s an amazing, amazing woman – I mean, this girl taught herself English by reading romance novels.

So she’s really, really determined and hungry for knowledge and she grew up in a place where being able to connect to the outside world was very, very difficult. In Saddam’s Iraq it was hard to get books, even, from the outside world – movies, things like that, things that we take for granted. And so when I met her, I was just blown away by how determined she was, how hard she worked at getting what she wanted and – I just wanted to see her get where she wanted to be, you know?

It was also interesting, you know, because [she was a] translator and then she got a job and we ended up being sort of colleagues – it was great, it was really fun. I remember once we were having coffee and just sort of both complaining about our jobs and talking about our jobs, and it was this great moment, in the middle of all this chaos in Baghdad – it was the summer of 2004 which was this really chaotic time – and things were starting to really spin out of control, and it was great to have a friend that you could just sit and have coffee with and just talk about – just have girl talk, you know (laughs)? Just talk about boys, and careers, and all this stuff that you might talk about with a girl friend here in New York City – but with somebody who had a completely different background and was finally getting a chance to engage with the world in the way that she always wanted to.

PRK: Did you have some sense during the war in Baghdad and also during some strife in Beirut – how does war affect the food that people make? Do they turn to it more for comfort?

AC: Absolutely – that’s absolutely what happens. People want foods that are familiar, they want foods that maybe connect to something in their past. And they like to have foods that they can share with others – that can be something that you can eat with others, maybe family foods, things that their family would make.

I’ll give you an example of this – a lot of what I write about in the book [is the] dichotomy between restaurant food and home cooking. Because a lot of what we Americans think of as Middle Eastern food is actually restaurant food and social food. If you go to a restaurant, you might have what’s called Mezza… they’re the sort of small plates of the Mediterranean… hummus, tabbouleh, baba ghanoush, these kind of plates – whereas at home, you’re going to have stews and pilafs and sauces and these kinds of things that you can eat communally around a big bowl. They’re very, very comforting, they’re very warm – these kinds of foods are what I ate a lot of in war zone situations, especially when you go into people’s homes.

So when you’re eating with people, when maybe it’s not safe to go to a restaurant, you might eat with people in their homes – you’re going to be eating a completely different kind of food. It’s going to be home cooking, it’s going to be comfort food, and it’s a completely different experience. And it’s great, it’s fantastic food.

PRK: How do women’s roles in the kitchen differ from Baghdad to Beirut to the United States? Do women consider it an outlet for creativity, or more of a dreary chore?

AC: The funny thing is, I’m not an anthropologist, I haven’t done an extensive survey, and I think it’s just the same in the Middle East as it is here. For some people it’s a chore and a burden and they hate it, but I know some people like that here in America as well (laughs). In some Middle Eastern families, the dad is the one who does the cooking, while the mom isn’t that into food and doesn’t want to be trapped in the kitchen. In some families everyone cooks together – it’s a mixed bag, it’s just like it is here. It depends more on whether it’s an old-fashioned family or a newfangled family – some families it’s just kind of everyone fends for themselves.

I mean, I think there is more cooking and eating around the dinner table, and probably in a more traditional part of Iraq, for example, or Lebanon, you would have a more traditional set-up where the mother makes the food and everyone eats and then she cleans up and everyone goes and watches TV or something like that – but you would have that in a more traditional part of the U.S. as well.

PRK: But then you also talk about street food – is that scene different over there then in New York, for example?

AC: It is – and New York is a particularly street food-oriented city, so I’m used to a very high level of street food, but it’s nothing like compared to what it is in Beirut, for example. In Baghdad, the street food scene – obviously when there’s a civil war, that’s going to change. Unfortunately, and what was really sad about Iraq was that you would see public life and particularly people who did things in public were sort of more – they were soft targets, they were the first people to be targeted. I write in the book about how restaurants and markets and stores and public places are where people connect and then go, where people of different types can be found together. And this is unfortunately one of the reasons why they’re the very first to be targeted in civil wars and by terrorists.

PRK: Is there anything else you want to add?

AC: People often ask me about the role of women in the Middle East and what it was like to be a female correspondent… I would love to be able to say that it was terrible being a female in the Middle East and it was terrible and I suffered greatly and everyone was mean to me – but actually, you have a great advantage as a woman. As a female correspondent – men can really only report on men, but women can report on men and women.

And so you have access to this world of domestic life, of families, of home and food and cooking, and I think a lot of Americans are really interested in that stuff. I wanted to write about everyday life because so much of what we see and hear about the Middle East has to do with conflict. Very, very seldom do we get to hear about everyday life – what are people’s everyday hopes and dreams? What are people’s fears? What do people say when they’re sitting around the dinner table together? I really wanted Americans to get a chance to almost sit at the dinner table with me and almost partake in an average family’s life and an average family’s conversation. So I hope that I’ve conveyed that in Day of Honey, because I want Americans to have that experience…

I think…90 percent of our lives are everyday life. We eat, we go home, we commute we work – and very rarely are these things depicted, not just in the media but also in novels or films or things like that. But they’re the texture of our lives. And people are really curious about the texture of life in a foreign country – or even in another part of the United States – because it’s where most of our life is spent: at the dinner table, in the kitchen, washing dishes, everyday things like this.

And there can be a real beauty to them – and another thing that’s really important about this, and I guess this is one of the most fundamental things I wanted to convey with Day of Honey, these everyday things have such a beauty to them and we often don’t appreciate them because we don’t think it’s important. We think, “My God! The revolution in Egypt! That’s what’s important! The war in Iraq – that’s what’s important! The financial collapse!” All of these things. And these things are important, and they do affect our everyday lives, but when you’re in a war zone, when your country is at war, you learn to really appreciate and really savor these everyday things, especially when you realize how fleeting they are and especially when they’re taken away from you. When you don’t even have a kitchen, you may really appreciate something that you hated before, like washing dishes or chopping vegetables.

***

Update: The New York Times came out today, Feb. 7, with a review of Day of Honey. It’s glowing…

Pingback: Tweets that mention Exploring comfort food and war in “Day of Honey” | Public Radio Kitchen | Blogs | WBUR -- Topsy.com