Here’s a foodie confession: several months ago, I had never tried tabbouleh. I had never cooked with coriander and I hadn’t pondered the savory application of cinnamon. When I thought of food from the Middle East, I thought of a single word: hummus.

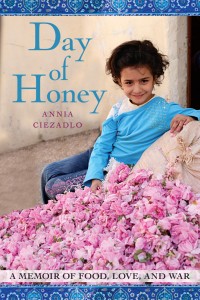

I’m pleased to report that all of that has changed rather dramatically, to the point where I’ve been trying – craving, even!- Middle Eastern food at least several times a week. The reason for that, plain and simple, is Annia Ciezadlo’s exceptionally, beautifully human Day of Honey, her new memoir of food in Baghdad and Beirut.

Ciezadlo, an American, moved to Baghdad as a reporter soon after her wedding to a Shiite Muslim – and soon after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime. It’s a strange time for her, to say the least – she has no real home for her new marriage, and only a tenuous grip on what it means to have a “home,” anyway (she was, for a period in her youth, quite literally homeless). So she takes solace in food: masquf and tanoor bread along the Tigris, iftarfeasts after Ramadan, tea and formerly banned spell-books on Mutanabbi Street. As conditions deteriorate and a civil war rises, Ciezadlo and her husband relocate to his homeland of Beirut – only to find that war follows them there.

In recent years, readers have gotten used to travelogues that seem to offer no real wisdom beyond the restorative power of being an upper-middle class white person doing yoga in a third world country(there’s a cute wink at such books in one of Ciezadlo’s chapter titles, which I won’t give away).

Day of Honey is immediately different. Food isn’t a path to self-discovery here, or anything quite so pat and treacly. I loved the book because of how unselfish an eater Ciezadlo is – she eats not for self-betterment, but to really know her new neighbors, to see Sunni, Shiite and Kurd alike as dining companions. I don’t think she’d see food as the key to peace, as this Christian-Science Monitor review seems to say – she simply sees it as the key to understanding, which is not quite the same thing.

For example, sometimes when I read about the Middle East, I feel like I’m reading a history book – but Ciezadlo makes her friends altogether modern and bright and vivid. They recite old rock songs and read romance novels, start up gay clubs and flirt shamelessly. And they eat: sometimes Yakjnet Sbanegh, but sometimes jello. Whole stories are contained in these foods – salads with day-old bread for lean times, delicate raw lamb for celebration. Pudding for fertility and fish for hot days along the river. And when things are really bad, and all hope is almost lost: hummus from a can.

Ciezadlo is terrified throughout her life in war, but she never seems fully aware of it – she lingers dangerously in front of open windows, tells friends on the phone that the gunfire they hear is fireworks, and, in one memorable instance, actually risks her life for pasta. Whatever numbness she acquires, however, leaves as soon as she takes a bit of foul, or mjadara hamra, or mlukhieh - she can spend pages describing their texture, their scent, the way hamudh tea tastes like “drinking old history books” and how pomegranate seeds can be melted into a sticky and tart molasses. Everything is hyper-acute – it’s like technicolor.

When I interviewed Ciezaldo last month, I described the cuisine she wrote about as the ultimate comfort food – the food that sustains families during times of great crisis, food that goes beyond restaurant falafel into something more primal, more earthy, more necessary. There was more to that assessment than I knew – the Lebanese even have a word for soul food, “akil nafis” which means, literally, “food is soul.” Perhaps the best example of this is one of Ciezadlo’s favorite meals, batata wa bayd, crumbled potatoes and eggs, “Lebanon’s moral equivalent of macaroni and cheese.”

Ciezadlo had spent hours attempting – and failing – to recreate this dish, its perfect, balanced, creamy mixture of eggs and onions and potatoes. Finally, in one of the book’s funniest scenes, she turns to her mother-in-law to find the solution: a long, watchful caramelization of onions, only then followed by chunks of cold and salty potatoes that are slow cooked in a heavy pot. Eggs are stirred in at the last second, almost like an afterthought, until the texture is creamlike, just heavy enough to hold the dish together.

Hungry yet? Luckily for you – and me – Ciezadlo includes her mother-in-law’s method for batata wa bayd in the substantial recipe appendix at the end of the book. Emboldened by its humble list of ingredients, I tried it out myself, adding some chopped rosemary and serving it next to wilted spinach. Now, I live a simple and safe and rather lucky life – I don’t expect to see Boston explode in war any time soon. But the dish spoke, too, to my more mundane stresses. It’s a meal that made me warm and full and happy. In the spirit of wishing that for everyone, Ciezadlo graciously allowed us to reprint the recipe, below.

Batata wa Bayd Mfarakeh

(Crumbled Potatoes and Eggs)

Serves 4 generously

Ingredients

10 ounces onions (about 2 medium-large), diced (about 2 cups)

2 tablespoons canola or olive oil

3 pounds russet or Idaho potatos (about 4 medium-large), peeled and cut into ½ inch cubes (about 4 cups)

1 tablespoon sea salt, plus more for salting potatoes and to taste

Optional: 2 tablespoons chopped fresh herbs such as oregano, rosemary, and/or thyme

8 eggs

Equipment

Medium-sized pot or dutch oven with a lid

- Saute the onions in the oil in a heavy or nonstick pot over medium heat. Stir frequently and do not let them burn. Once the onions begin to soften, after 2 to 3 minutes, cover the pot and turn the heat down to medium-low. Check the onions and stir every 10 minutes or so to keep them from sticking and burning. Do not let them brown at this point; you want them to caramelize very slowly. When they start expelling a lot of liquid and are turning translucent, turn the heat down as low as possible.

- While the onions are cooking, sprinkle the potato cubes generously with salt, toss, and let them sit for about 5 minutes. Rinse very well under cold water.

- After about 30 minutes, the onions should be starting to turn dark gold. Increase the heat to medium and remove the lid to evaporate as much of the liquid as possible. Add the tablespoon of salt and potatoes and mix. If you’re using fresh herbs, add them now.

- Turn the heat to very low and cover. Sweat the potatoes until they are soft – usually10 to 15 minutes – stirring gently and tasting every so often. If you like them crispy, turn the heat up, add a bit more oil, and let them crisp for a few minutes between stirs. The potatoes are done when they just begin to disintegrate around the edges and you can pierce them easily with a fork. Taste and adjust the seasoning.

- Crack the eggs directly into the pot. Stir until they just begin separating into creamy curds. Take the pot off the heat and keep stirring until the eggs are done (they will continue to cook for a minute or two in the pot). Taste and adjust the seasoning with salt, pepper, or whatever else you like.

Book to read for the summer