Published October 26, 2010

There’s another angle to Norton’s “no friending” policy that I barely touched on yesterday on Radio Boston.

After the suicide of Phoebe Prince, the South Hadley girl thought to be a victim of relentless bullying, the state adopted ambitious guidelines for seeking out and punishing bullies.

It’s a new paradigm that injects adults into the playground power imbalance. The guidelines encourage teachers to be vigilant — both on campus and off — and requires them to report cases of bullying to teachers and administrators.

What's a teacher to do?

A lot of that bullying doesn’t happen on the playground, though. On the home page for Norton Public Schools is a link to a Facebook page called “End Cyberbullying,” a sign the school is serious about stopping virtual terror.

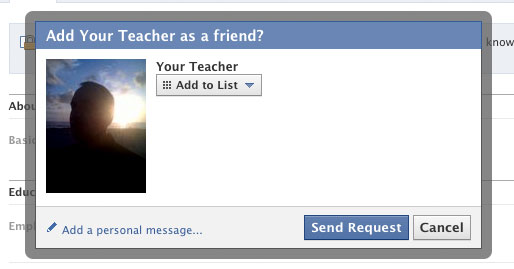

With a new policy that bans teachers from “friending” their students on Facebook, Norton is trying to set clear boundaries — fraternizing with students outside the classroom is inappropriate, virtually or otherwise.

But that means teachers aren’t allowed to be where a lot of the bullying is.

“There are some real concerns about what’s going on in the world of social media in general. How are teachers supposed to understand that issue if they’re cut off from it?” said Christopher Ott of the ACLU of Massachusetts.

Teachers like Lyndsy Shuman, the debate coach in Maine I interviewed yesterday, operate in a gray area. When she stumbled upon students engaging in a nasty back-and-forth on Facebook, Shuman felt powerless, unsure of her own role.

Does she intervene in the flame war? Does she call a school administrator? Would she be accused of inappropriate behavior for monitoring students online? (Shuman decided to hide the updates altogether.)

The Norton schools superintendent said the new rules are under review and could change in a few weeks. Perhaps more useful for teachers would be a virtual guidebook — rather than a “no entry” sign at the door?